Collegiate Football Begins…Again

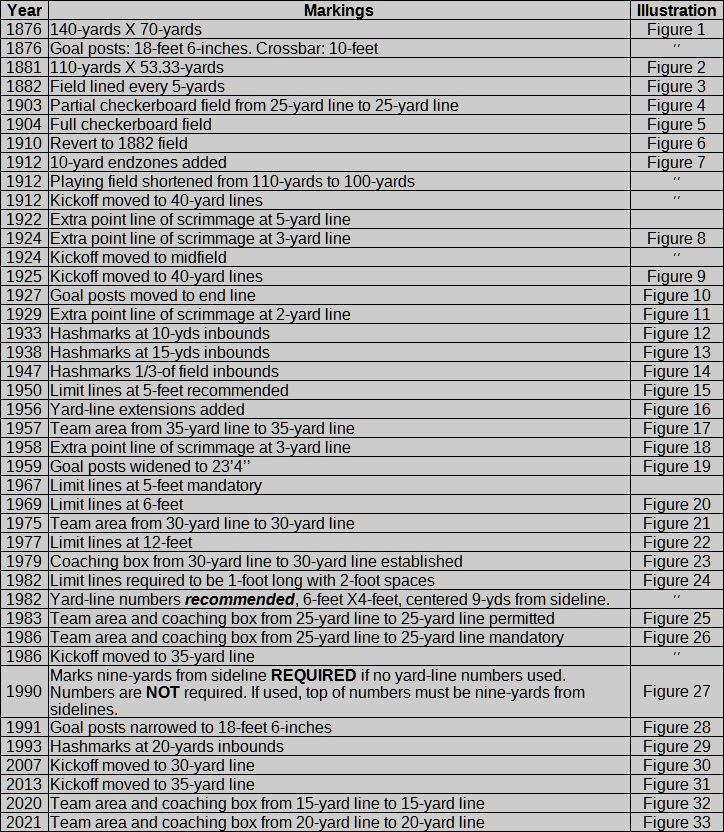

The game that is hailed as the birth of American football in 1869 more closely resembled soccer. In late 1876 the Intercollegiate Football Association adopted Rugby Union rules with a few modifications, including the size of the field. These illustrations are an attempt to catalog the history of (mostly) required markings on college football fields using Parke Davis' 'FOOTBALL The American Intercollegiate Game' (1911) and David Nelson's 'The Anatomy of a Game: Football, the Rules, and the Men Who Made the Game' (1994), as well as Spalding and NCAA rule books. Special thanks to Tim Brown and his website footballarchaeology.com. All measurements are given in United States customary units of yards, feet, and inches.

You can also view this gallery of illustrations here. There’s a TL;DR table summarizing this article at the end.

Rugby Not Soccer

Field and Goal Dimensions

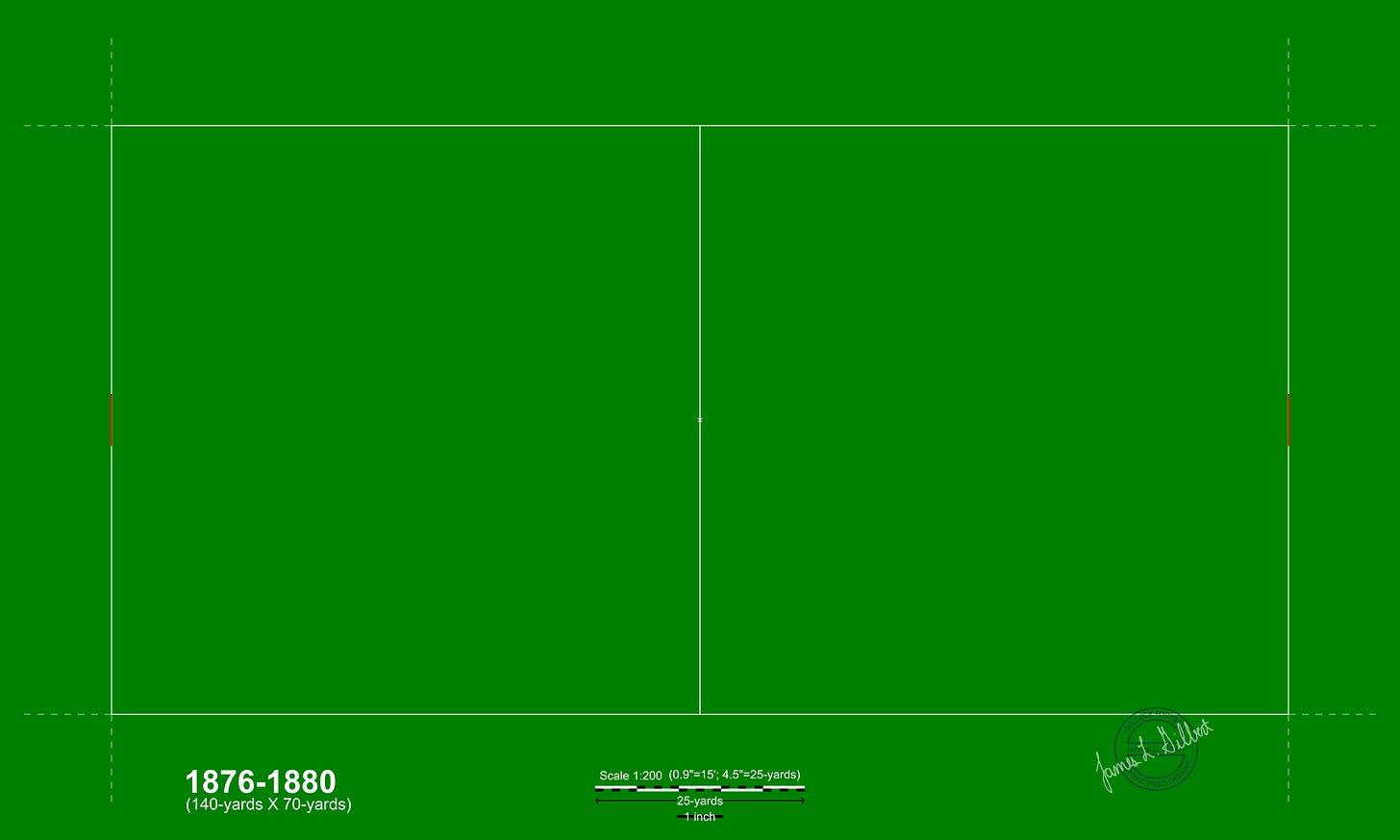

The Intercollegiate Football Association met in November 1876 to draft rules. The rules were those for Rugby football, with a few exceptions, one of which was the size of the playing surface (Figure 1). While there was no rule stating the size of the field in Rugby, IFA's Rule 60 required a field measuring 140-yards by 70-yards (420-feet by 210-feet). (Walter Camp proposed a slightly modified field in 1879 (400-feet by 200-feet) that was rejected.) Goal posts were set at a width of 18-feet 6-inches and the crossbar at a height of 10-feet.

Out of Bounds

What we now call sidelines were originally called touch or bounds lines and a ball in that area was said to be in touch. A loose ball in touch was only dead once it was recovered. Battles for loose balls could be quite dramatic and regulations didn't require clearance from attendees around the field of play.

Goal Line

The area beyond the goal line was in goal. There was no need of an end line beyond the goal line because the only way to score on the ground was by carrying the ball past the goal line and touching the ball down.

Touch-in-Goal

The dashed lines represent extensions of the touch and goal lines, marking the area known as "touch-in-goal", and wouldn't necessarily be marked on the field. A ball entering the touch-in-goal area was automatically dead, i.e. unlike other areas of the field the ball did not have to be downed. The team whose touch-in-goal the ball entered would drop kick the ball to the opponent from the 25-yard line. This is called a kick-out. Safeties and touchbacks would be distinguished later. The kick-out option after a touchback would be eliminated in 1914.

Extra points

What we now call an extra point attempt was initially called a “try at goal” and there was no pre-determined spot or yard line from which this would be attempted. There were initially two options to spot the ball for the "try". The ball could be walked out from beyond the goal line into the field of play, perpendicular to where the ball crossed the goal line for a touchdown, and as far from the goal line as the scoring team wanted. Or, if the ball crossed the goal line towards the sideline the scoring team could "punt-out" the ball no closer to the goal posts than where the ball crossed towards a teammate who could score by 1) fielding the punt and running the ball across the goal line, 2) immediately dropkick it, or 3) fair catch it and attempt a free kick. The punter could move into the touch-in-goal area voluntarily or a penalty could move the punter 5-yards horizontally into the area.

Changes Are Afoot

After only four years (plus a couple of games in 1876) the dimensions of the football field changed.

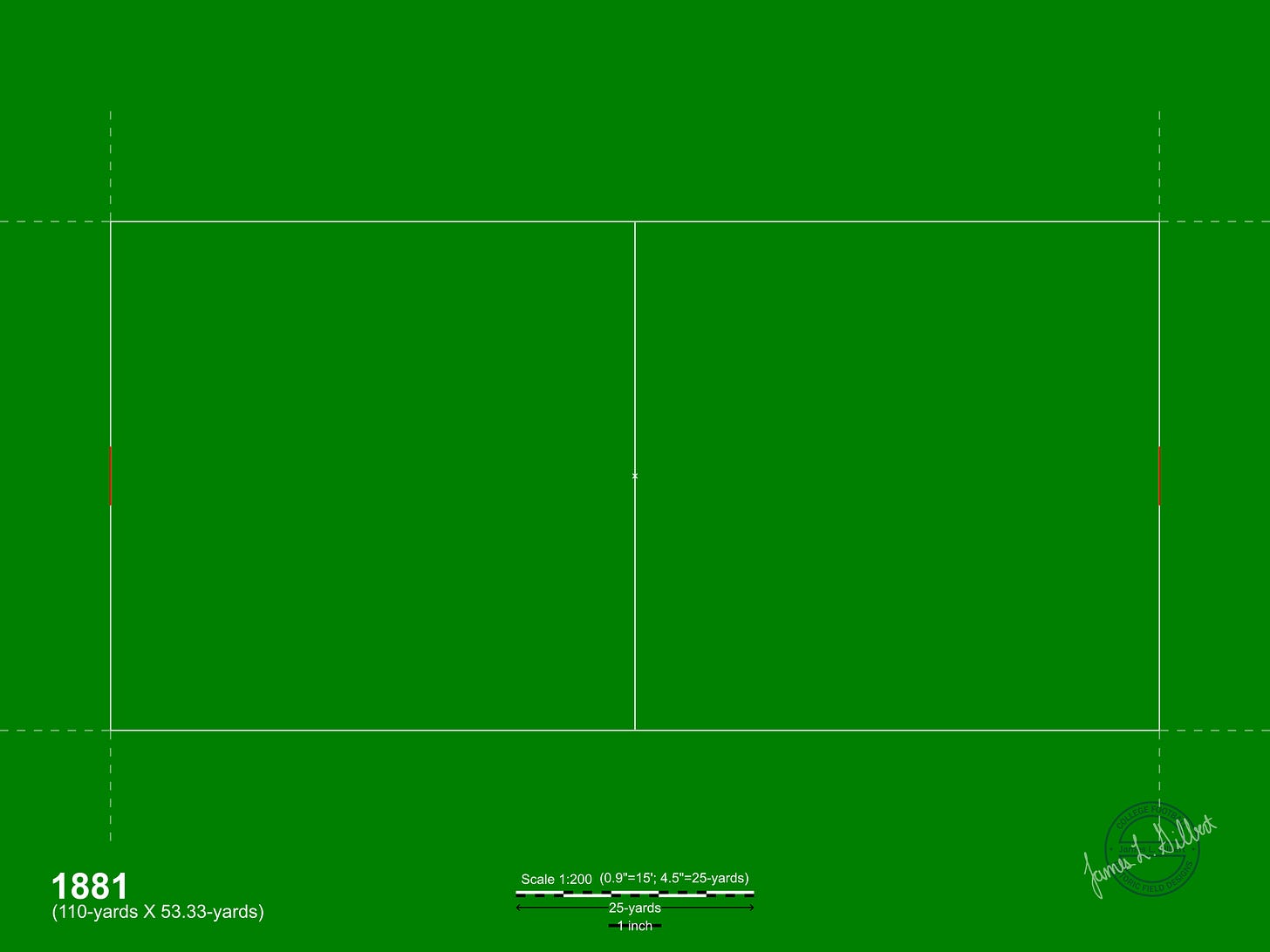

For several years, Yale requested the number of players per side be decreased from 15 to 11. In 1880, this rule was finally changed. While the number of players was about 75% of the original, the field size remained the same. Whether the field was now deemed too large for the reduced number of players or there was another reason, in 1881 the field's width and length were both reduced to about 75% of their original dimensions. The length of the field (Figure 2) was reduced from 140-yards (420-feet) to 110-yards (330-feet). The width was changed from 70-yards (210-feet) to 53.33-yards (160-feet) where it remains today.

It was noted at Harvard that a field of these dimensions would now fit within the track on Jarvis Field and initial plans were made to play that season's games there. This decision was later reversed, and Harvard did not play on Jarvis Field in 1881.

Now We’re Cooking: Gridiron Football

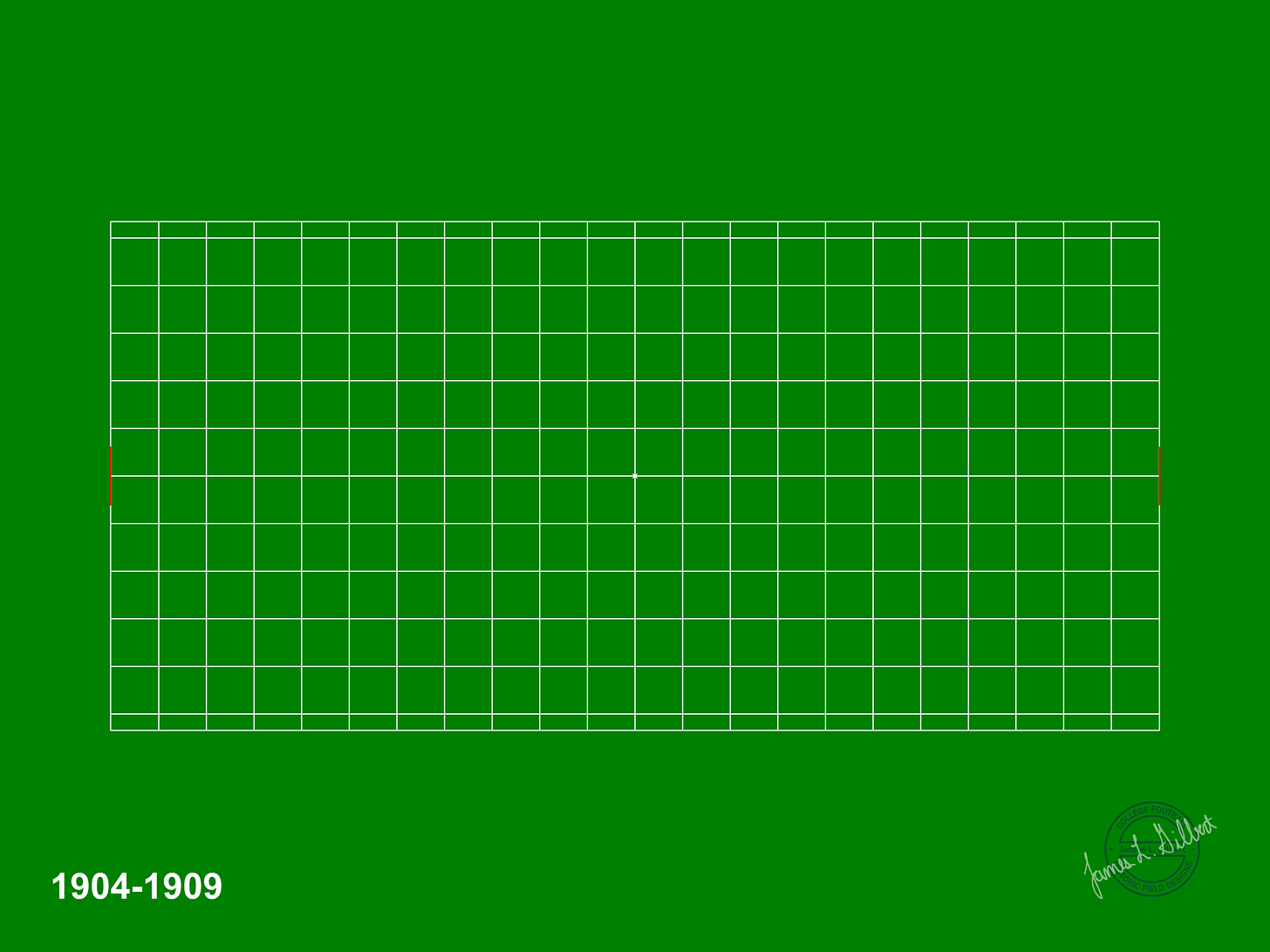

In response to the block game strategies of 1880 and 1881, which saw teams maintaining possession of the ball without attempting to score so that the game would end in a tie, the rules makers required the team possessing the ball to forfeit possession of the ball if they had not advanced the line of scrimmage five yards, or conversely lost 10-yards, after the player had been downed in three consecutive plays.

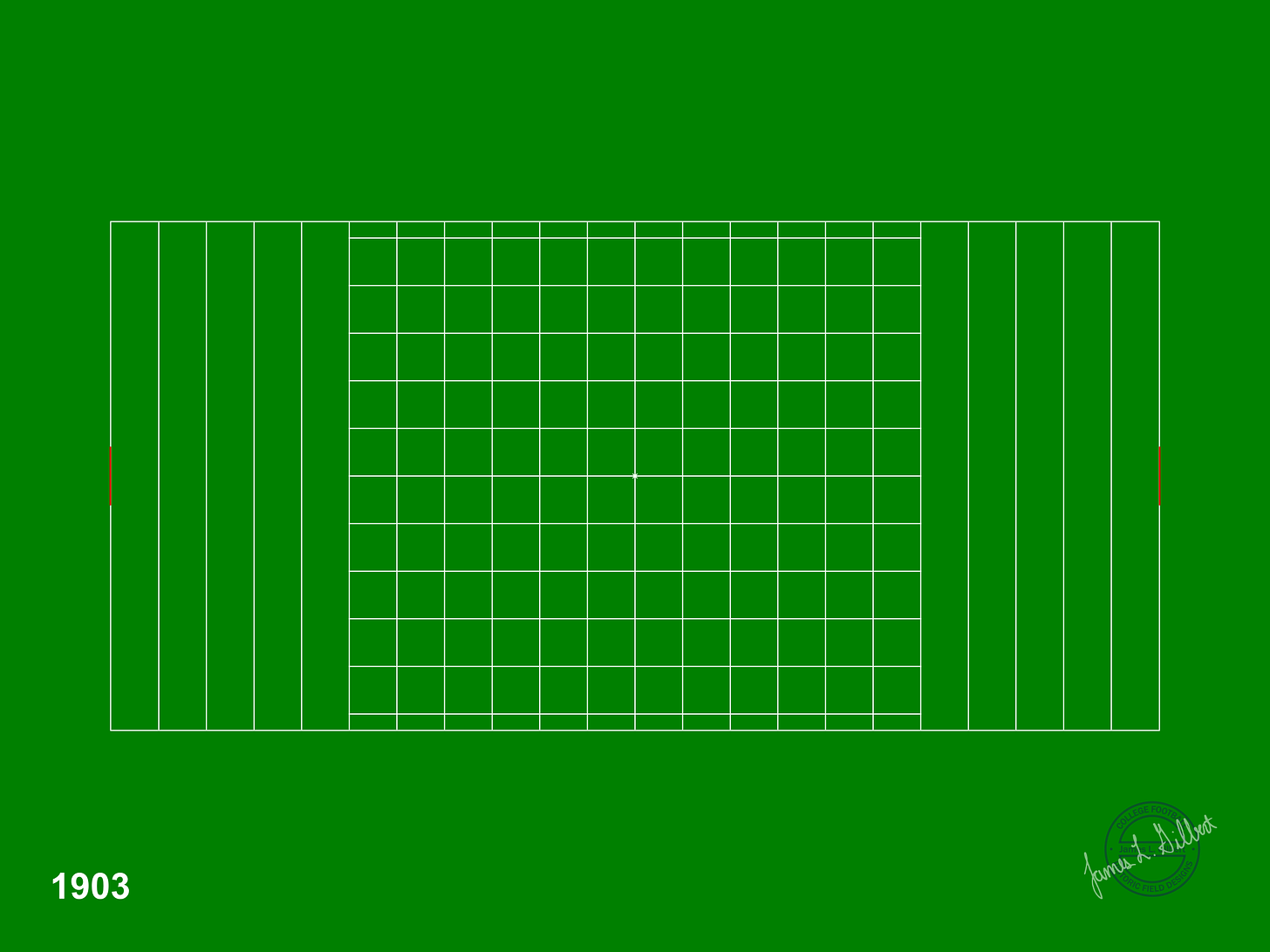

This is the field (Figure 3) where the term "gridiron football" comes from.

Football's Checkered Past

Earlier rules prevented the player who received the ball from the snapper to advance the ball. When that rule was changed, the player had to move laterally 5-yards before advancing the ball. In 1903 this rule only applied to the area of the field (Figure 4) between the 25-yard lines and the whole field from 1904-1909 (Figure 5).

Going Back

In 1910 the field reverted to the late 19th century design (Figure 6).

Along with many rules changes meant to open up the game and make it safer, the first player to receive the ball from scrimmage was now able to cross the line of scrimmage at any point on the field so the lines 5-yards apart from goal line to goal line were no longer needed.

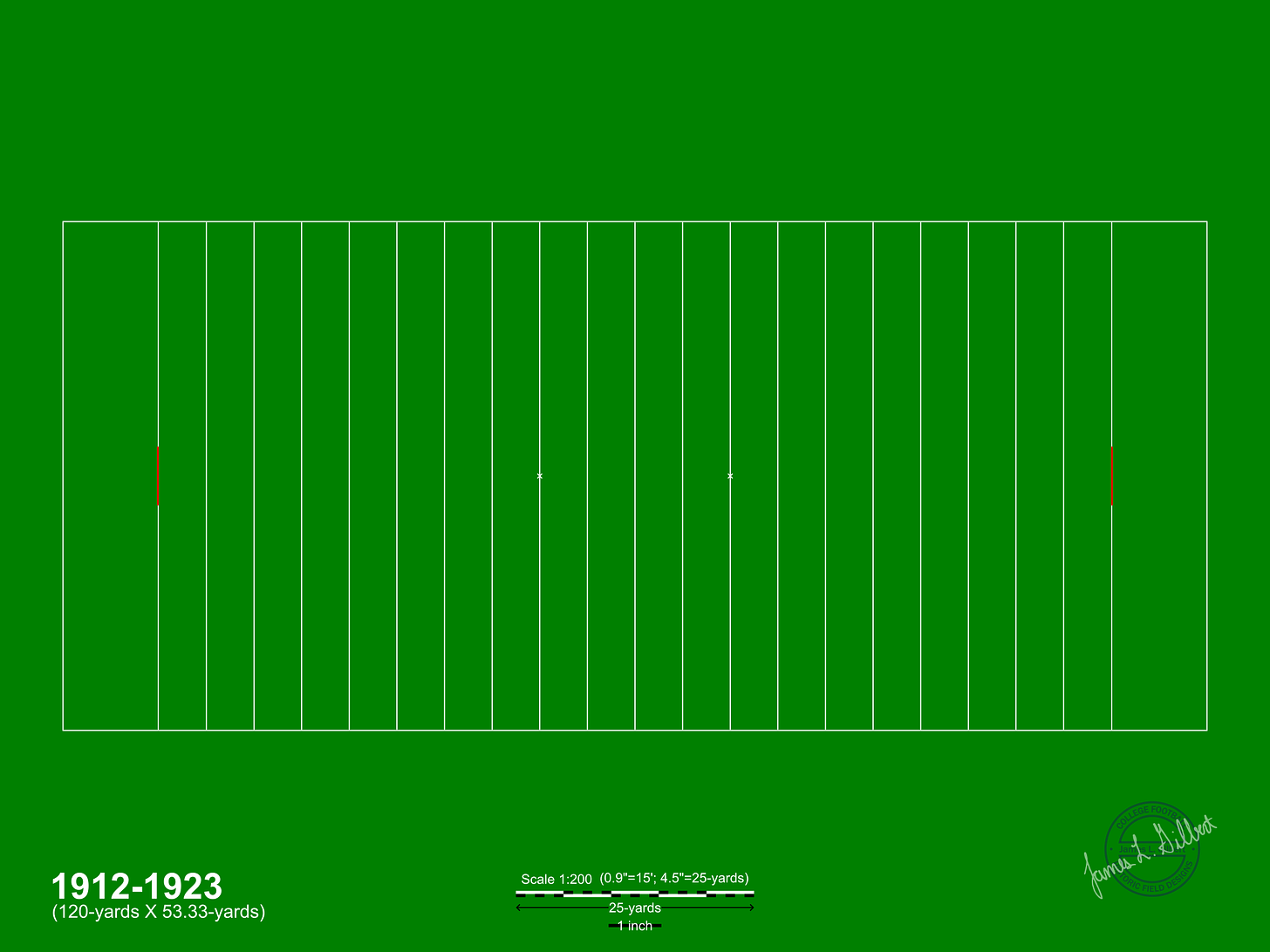

Entering the Zone

Before 1912, a forward pass (legalized in 1906) completed beyond the goal line resulted in a touchback. In a continuing effort to grow the passing game the rules committee created the “end zone”, a 10-yard-deep area in which a caught forward pass was a touchdown. This necessitated shortening the field of play by 10-yards and would be the last change to the dimensions of the field (Figure 7). The kickoff spot was moved from the 55-yard line to the 40-yard lines. Discussions to move the goal posts to the new end lines were not successful.

The punt-out was eliminated from the rule book in 1920 and in 1922 the "walk-out" was eliminated (see 1876-1880). For 1922-1923 the line of scrimmage for extra point attempts was the 5-yard line.

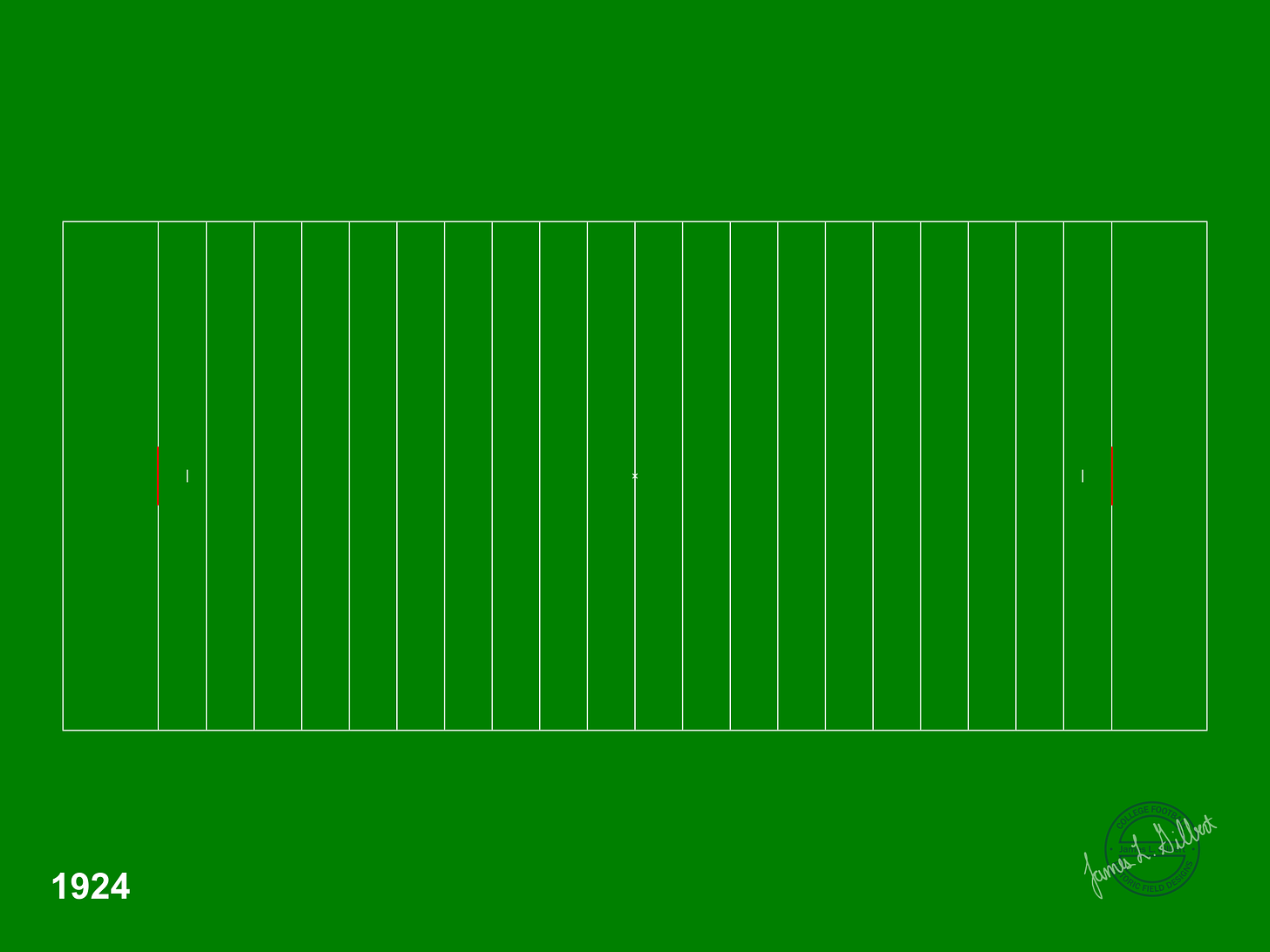

No Tee for You

Kicks from the ground had always been placed on a tee of loose ground or a teammate’s shoe (and later on, off a helmet), but the rules in 1924 forbid the use of a tee and the rules committee believed there would be a concomitant reduction in the distance of kickoffs therefore the kickoff line was moved to the 50-yard line (Figure 8).

The extra point attempt line of scrimmage moved from the 5-yard line to the 3-yard line.

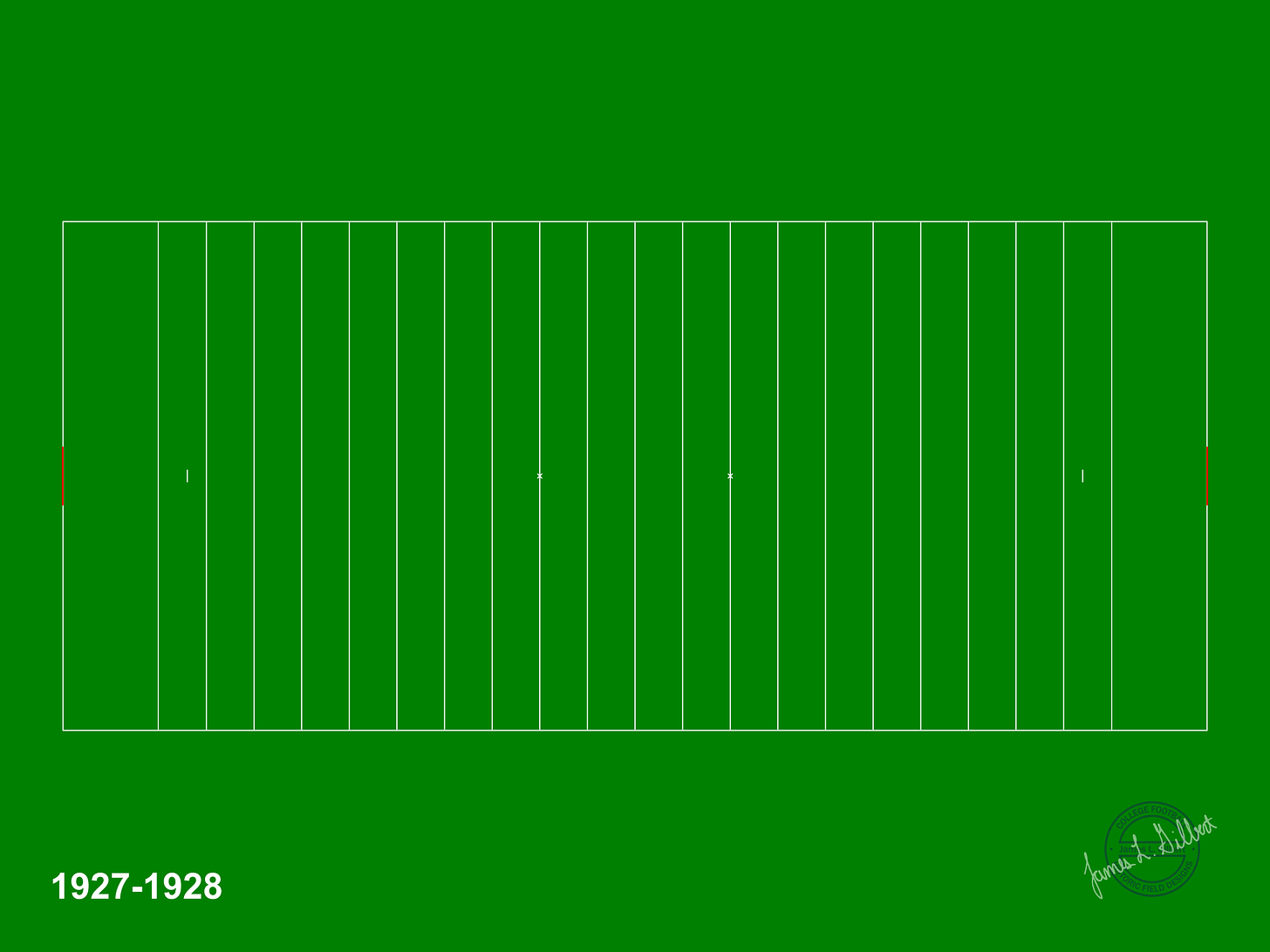

Because more kickoffs were touchbacks the kickoff yard-line was moved to its previous spot (Figure 9).

Moving the Goal Posts

Though moving the goal posts from the goal line to the end line (Figure 10) was discussed in 1912 when the end zones were added, it wasn’t until the extra point attempt line of scrimmage was set at the 5-yard line in 1922 that rule makers finally determined that this kick was too easy. Added benefits the rules committee noted were teams didn’t have to punt from behind the goal posts and a safer game on the goal line. The NFL followed suit, but in 1933 moved the goal posts back to the goal line where they would remain until 1974.

The justification for moving the extra point line of scrimmage from the 3-yard line to the 2-yard line (Figure 11) was to give the defense a better chance of blocking or otherwise altering the attempt.

After the goal posts moved to the end line in 1927 allowances were made to widen the goal line or add an extra line to signify to the crowd the importance of the goal line even though the goal posts had moved. The NFL still requires an 8-inch wide goal line.

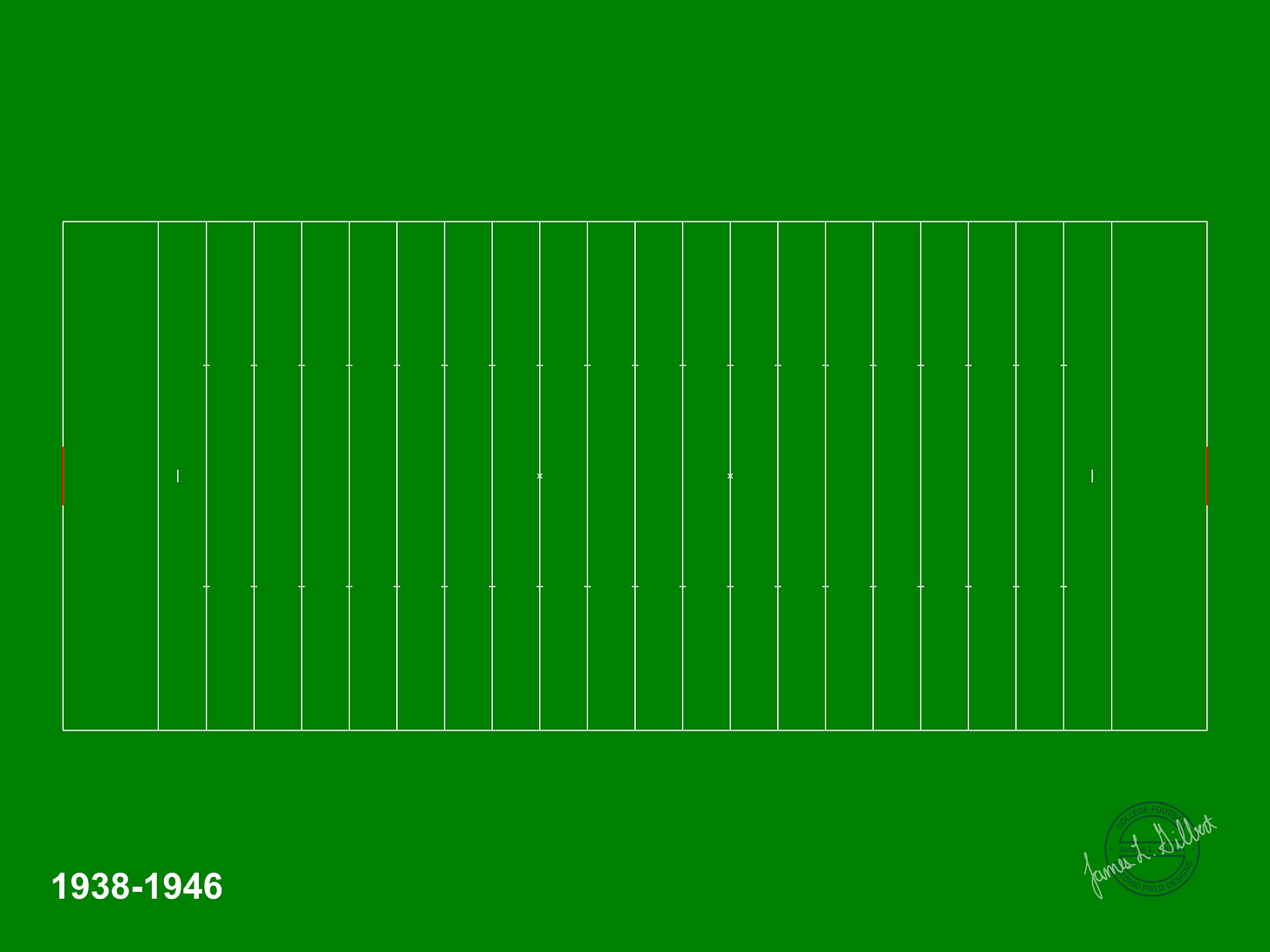

#Hash Marks

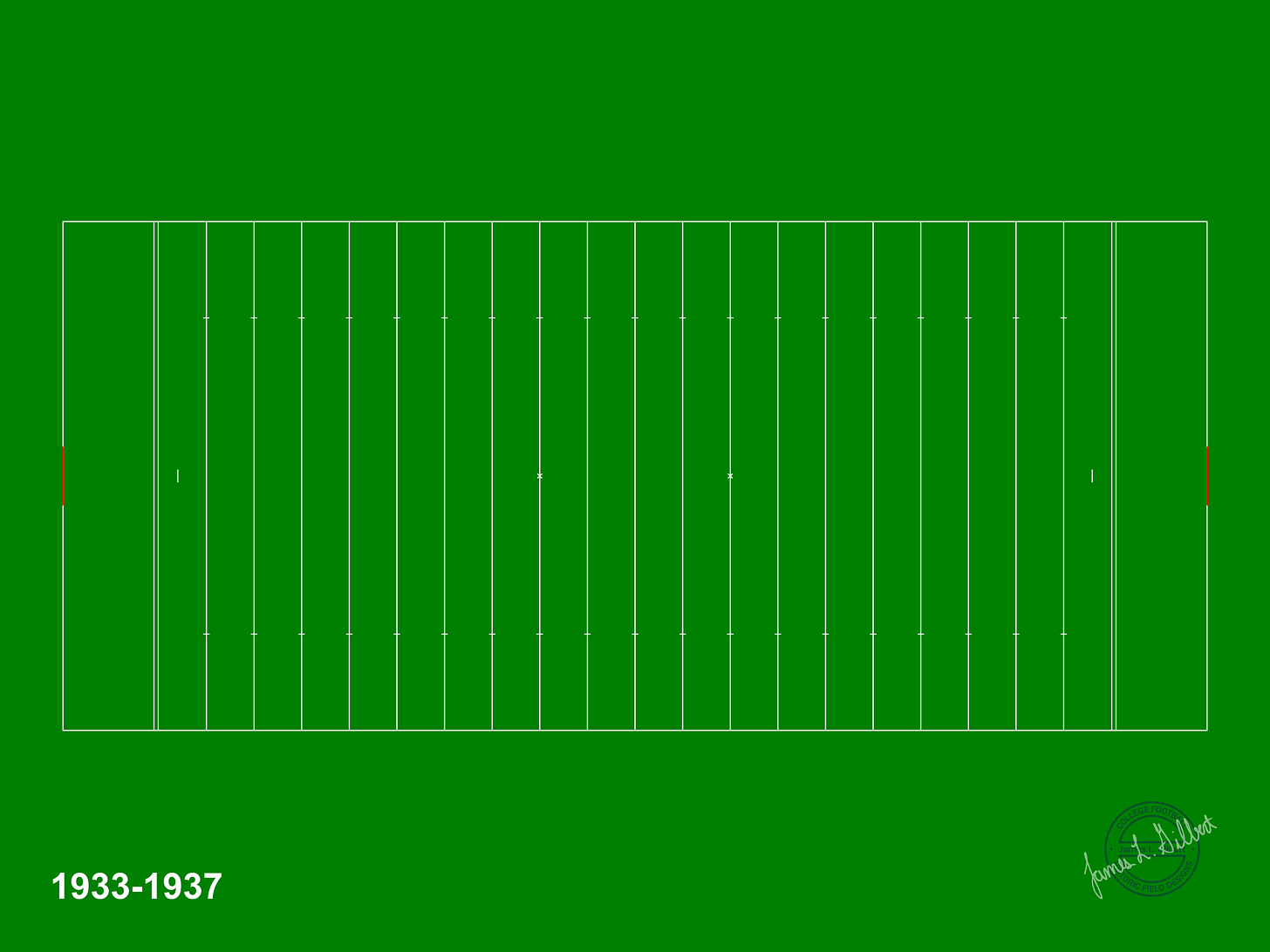

At football’s inception a play ended when either a ball carrier yelled “Down!” or was no longer mobile as adjudicated by the official. The next play would start wherever the ball was downed on the field, regardless of the distance from the sidelines. Teams even had sideline plays for that area of the field. When the ball was downed out of bounds the rules for starting the next play evolved over the game's first half-century. The play after the ball went out of bounds could start within a few yards of the sideline all the way to 15-yards inbounds. The 1933 rule addressed these issues by placing at 10-yards inbounds (Figure 12) any ball downed within 10-yards of the sidelines or out of bounds.

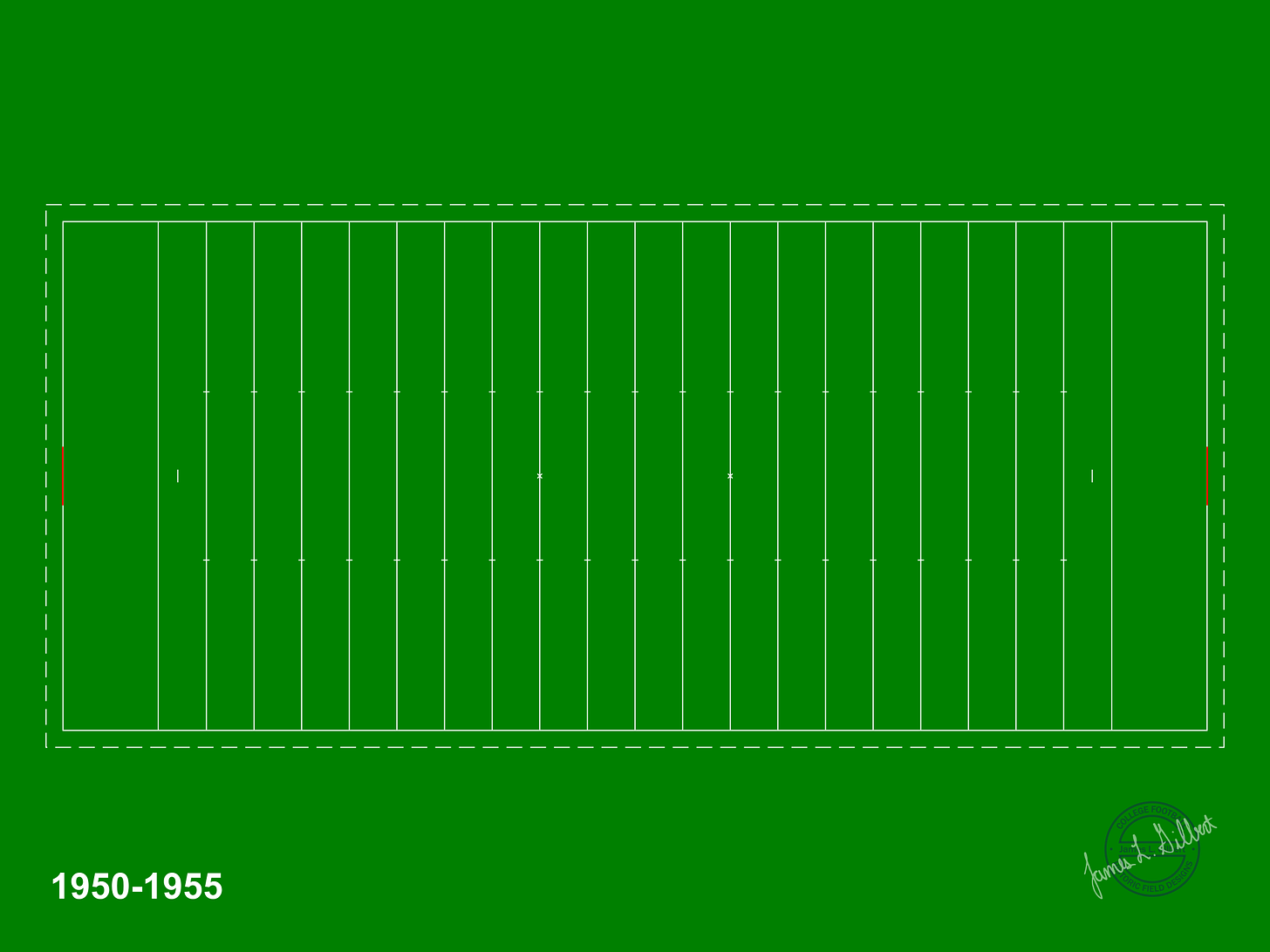

The only rules changes affecting the markings on the field from 1933-1947 were the inbounds lines or “hash marks”. They were moved in an additional 5-yards (Figure 13) and then another 8-feet 4-inches (Figure 14).

Although the vote of coaches earlier in 1947 on various rules proposals favored moving the hash marks 20-yards inbounds, that would not happen for another 46 years.

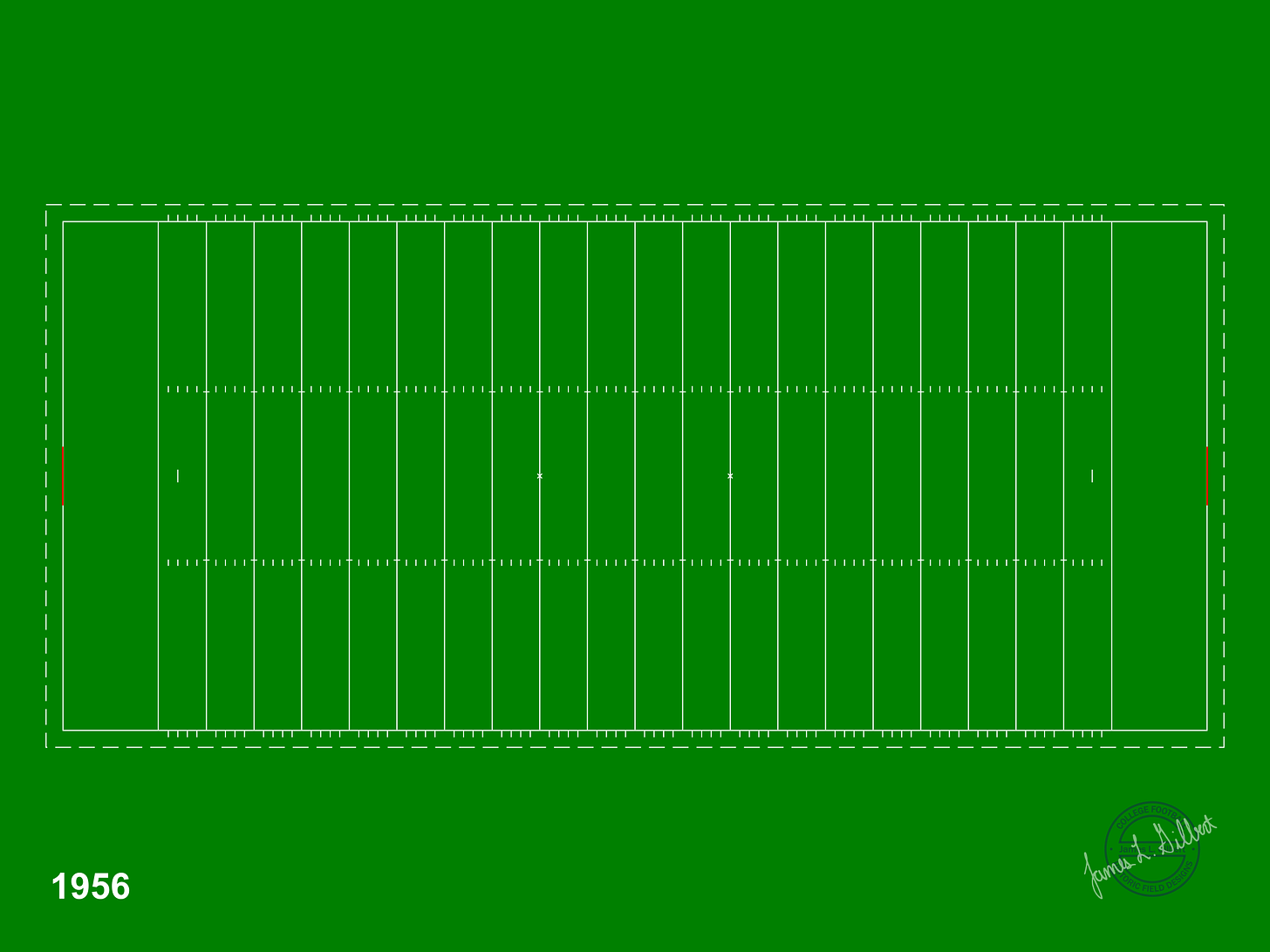

Take It to the Limit

No rules expressly forbid attendees to keep a certain distance from the field of play. While some institutions placed ropes or fences around the field, many did not. To keep fans and media safer and prevent interference with game operations the rules committee suggested a 5-foot “limit line” around the field (Figure 15). This would not become mandatory for 17-years.

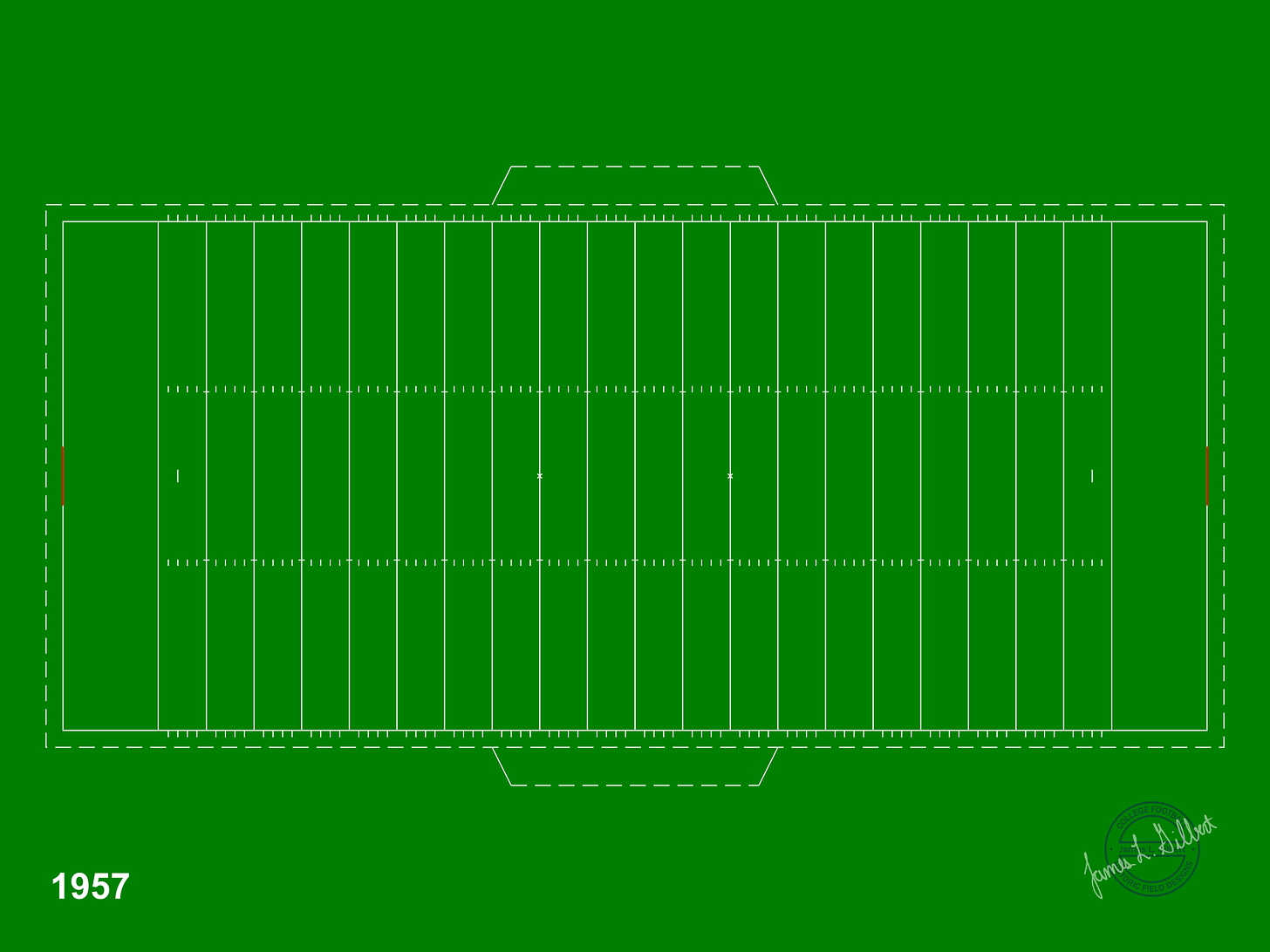

In 1954 a Waukesha, WI man convinced the local high school to paint a yard marker for every yard on the field in line with and perpendicular to the hash marks and down each sideline (Figure 16). A local college played on the field the next day. Eventually the lines appeared on a nationally televised major college game and within two years the markings were mandatory for all colleges.

For a more thorough discussion of the markers more commonly known as yard-line extensions see Remembering John Lockney: Football’s Forgotten Man.

A 1902 rule permitted 5-team members to walk up and down the sideline while all other team members and support staff were to remain seated during play. While this rule was eventually eliminated a designated “team area” wasn’t created until 1957 (Figure 17). This rule was meant to resolve the issue of coaches and players running up and down the sidelines.

Going for Two

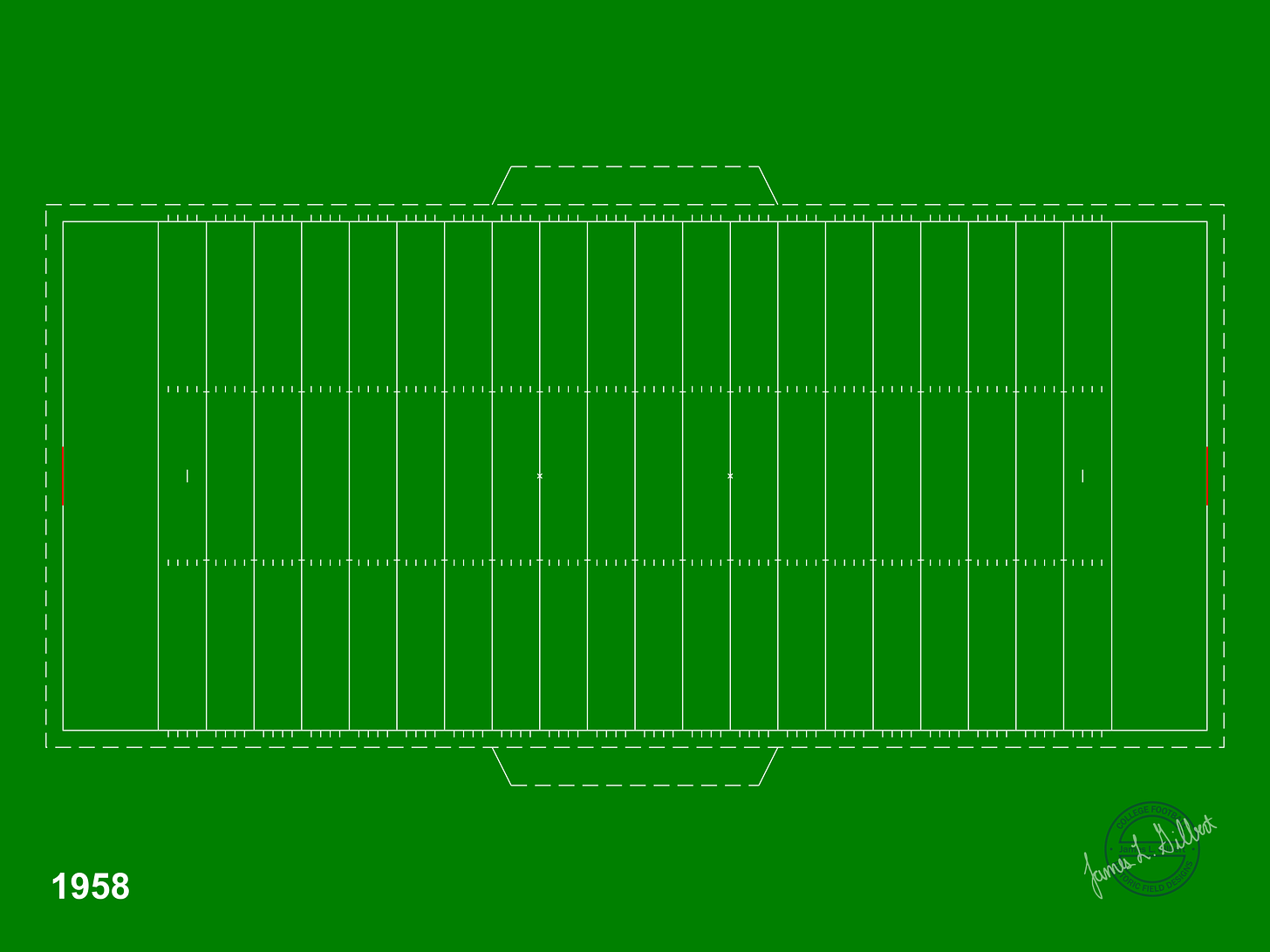

The two-point conversion after touchdown was instituted in 1958 in an attempt to increase scoring and fan interest in the game. As a concession to the defense, the conversion play would now begin at the 3-yard line (Figure 18).

Moving the Goal Posts…Again

In 1940 it was suggested to the committee to increase the number of field goals by widening the goal posts. A coaches survey after the 1958 season indicated a desire, by nearly 2:1, to move the goal posts back to the goal line. The coaches weren’t asked about widening the goal posts. The committee was not going to change the location of the goal posts and chose the new width (Figure 19) because 24-feet was the longest piece of manufactured lumber available.

Responding to complaints received by the National Association of Collegiate Commissioners about players and staff obstructing the view of spectators, the 5-foot limit lines around the field of play were now mandatory, 26-years after a 3-foot limit line was initially proposed to the rules committee.

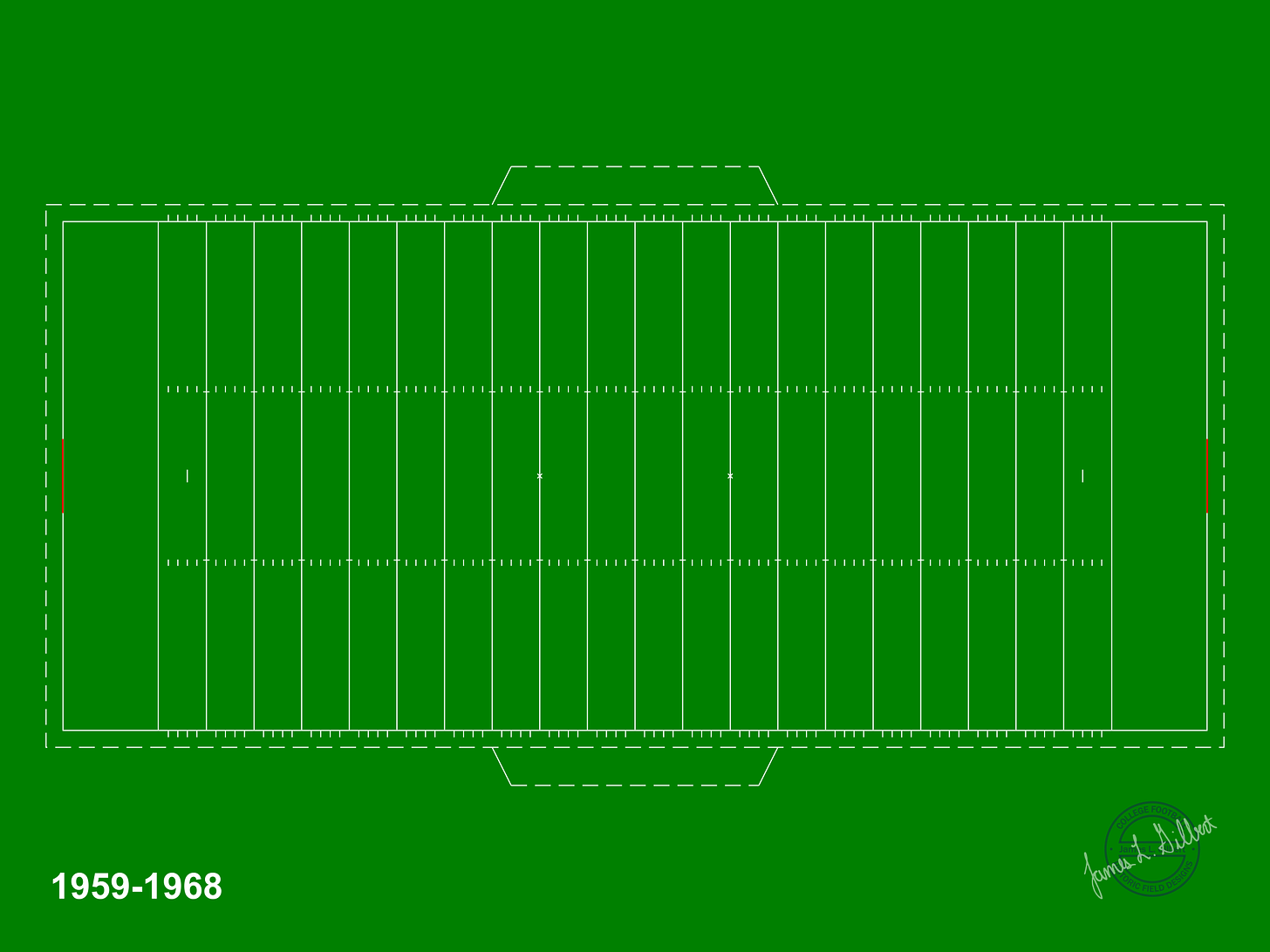

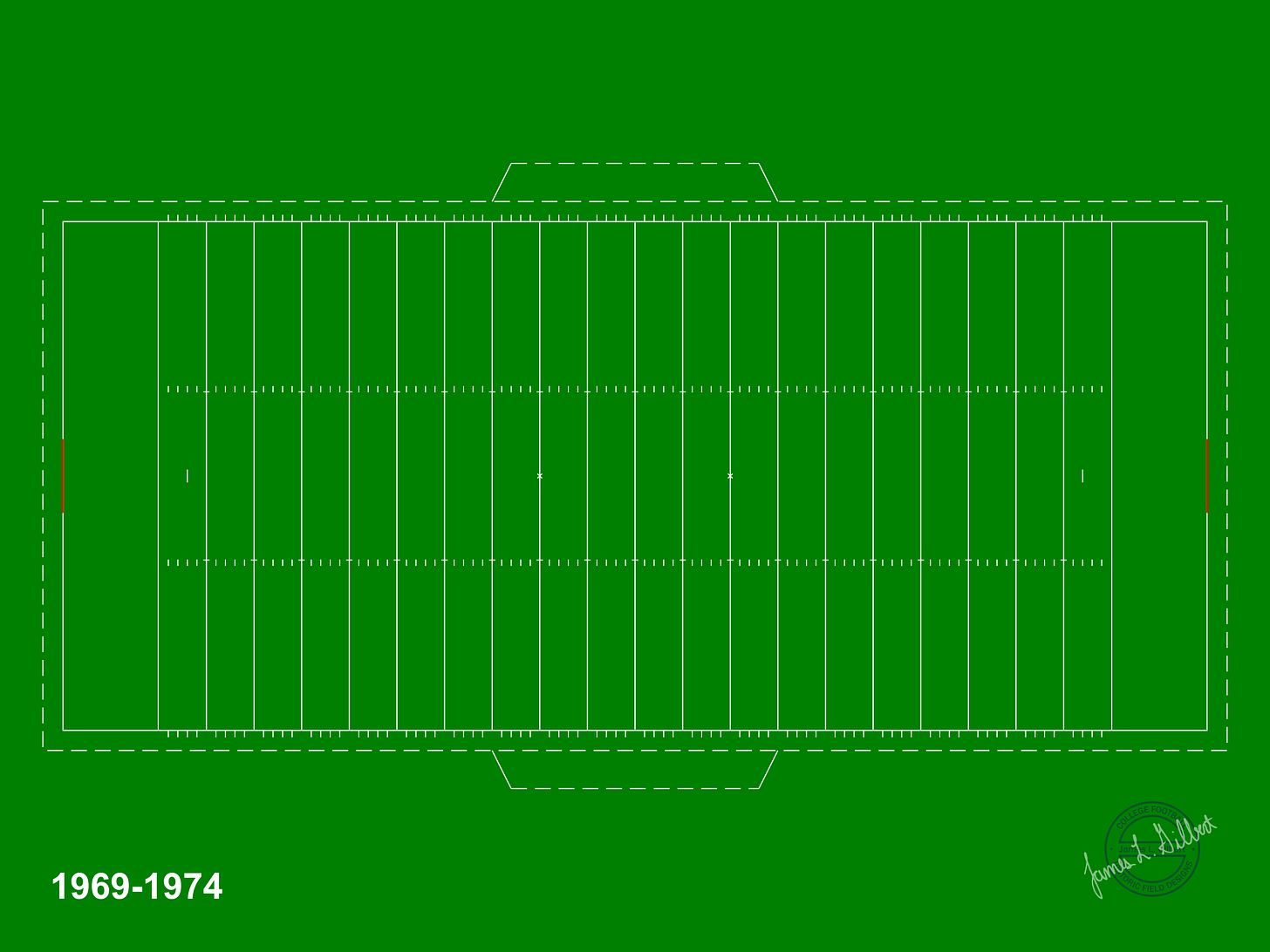

The only rule change of the 1960s that affected the field markings was a slight increase in the distance of the limit line (Figure 20).

Elbow Room

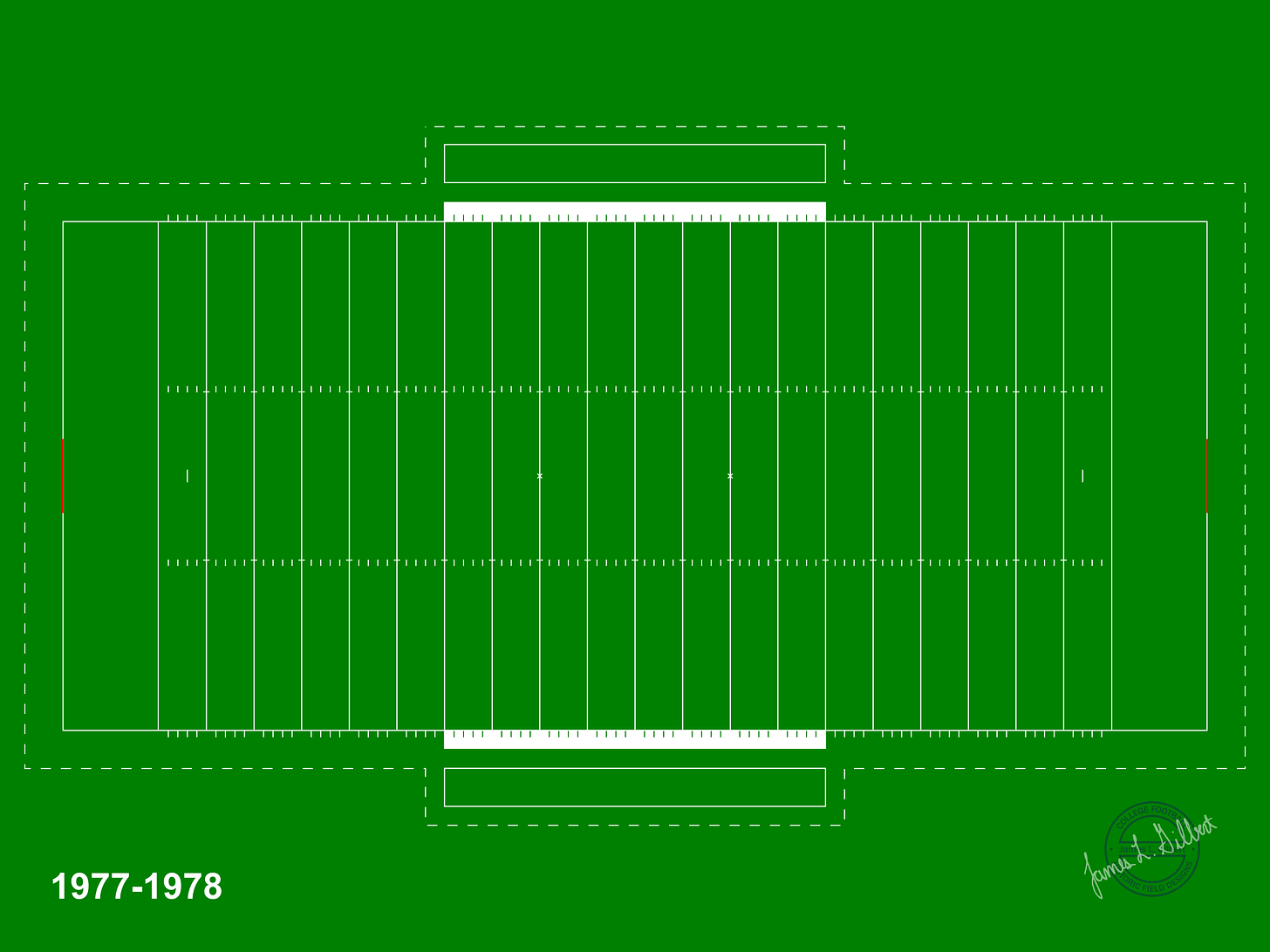

The increased number of players and staff as well as recruits necessitated an enlargement of the team area. It now stretched from the 30-yard line to 30-yard line (Figure 21). Media members objected any time the limit lines and team area changed.

Stadiums too small for a 12-foot limit line and/or a 4-yard deep team area (Figure 22) are allowed to halve those dimensions.

Coaches are now permitted in the area between the limit line and 30-yard lines. The coaching box is designated by diagonal lines (Figure 23).

NCAA Guidelines for Effective Sideline Control

Rule 1, Section 2, Article 3:

Limit lines shall be marked with 12-inch lines and at 24-inch intervals 12 feet outside the sidelines and the end lines, except in stadiums where total field surface does not permit… Limit lines shall be four inches in width.

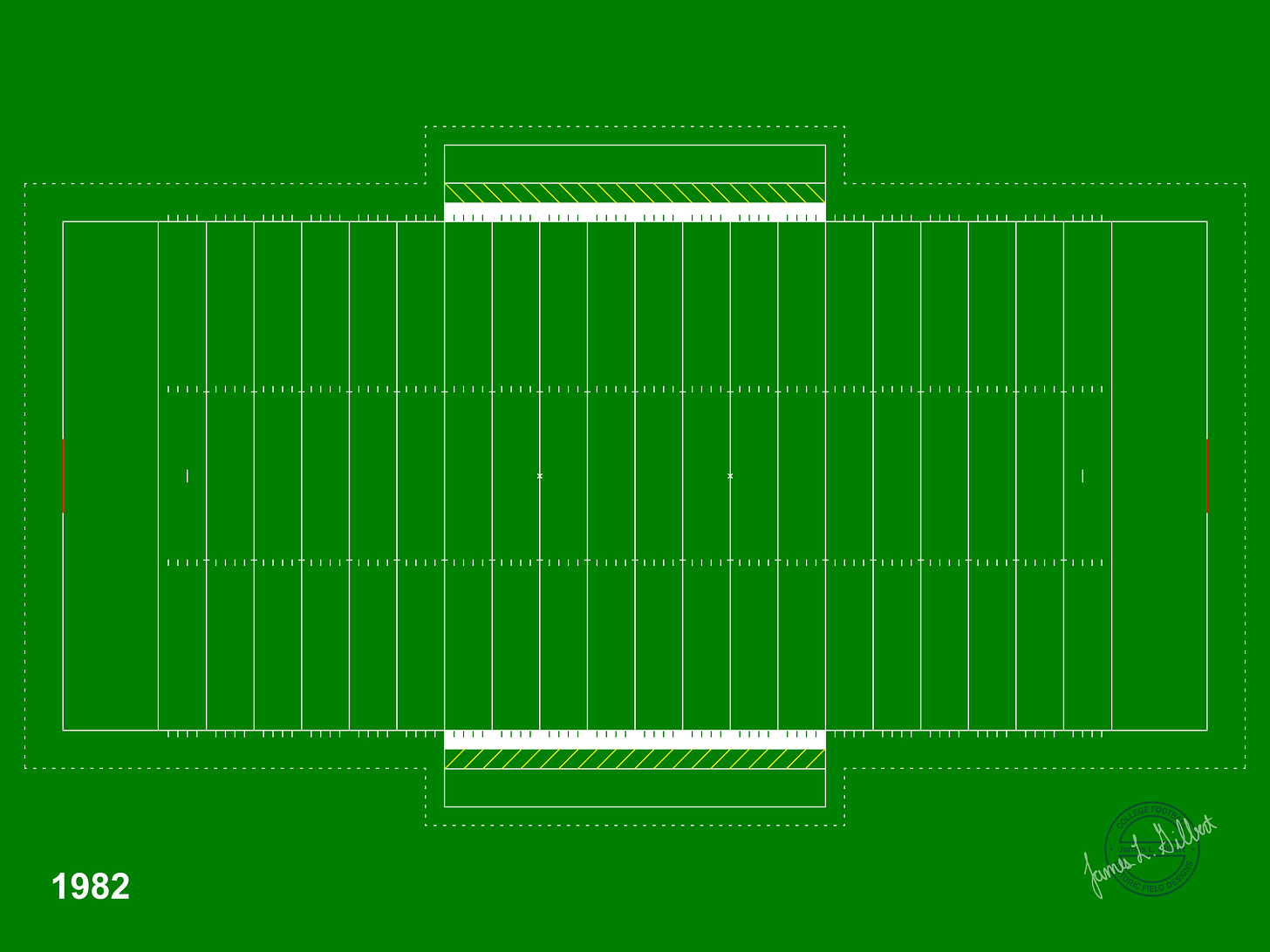

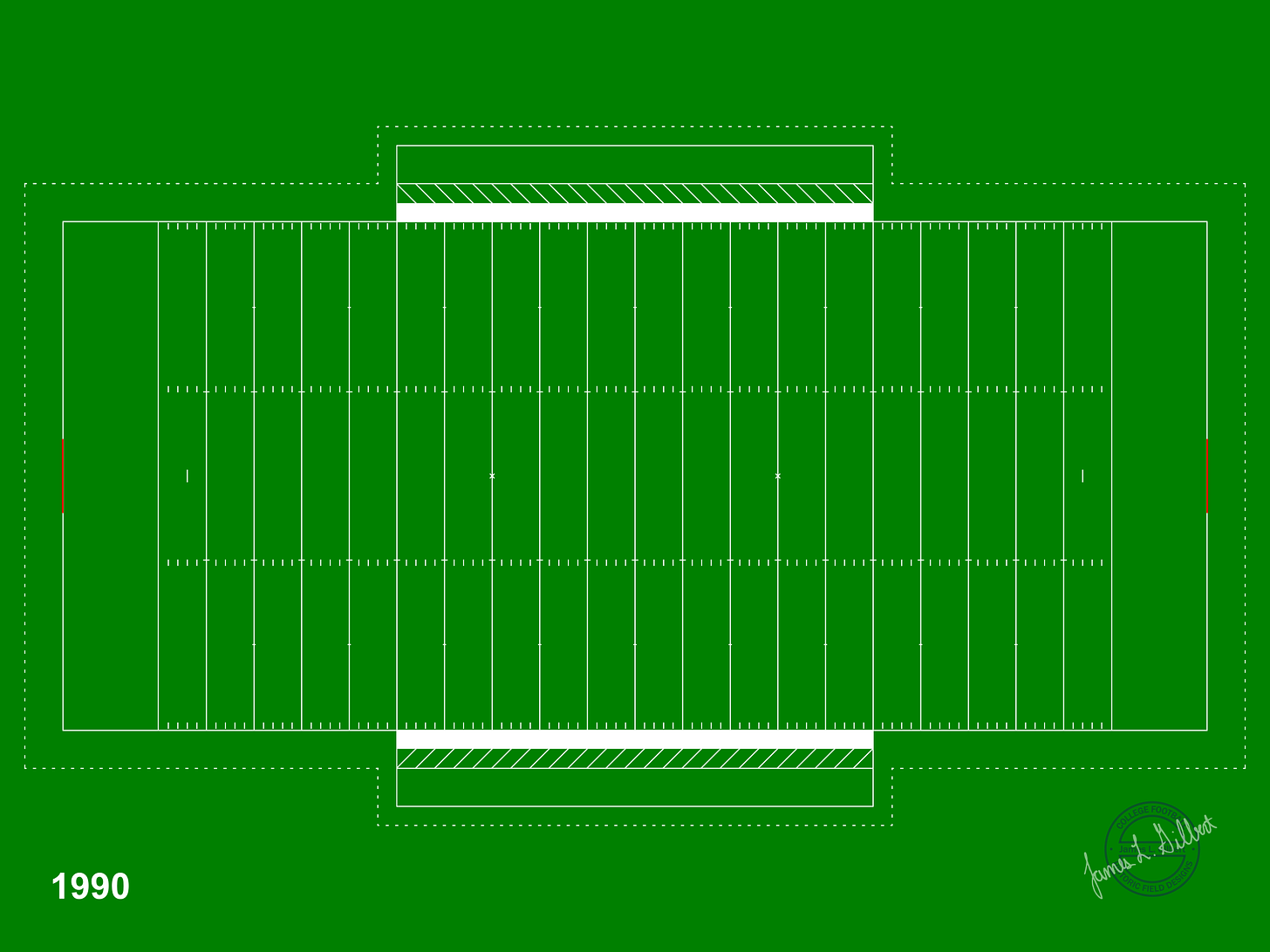

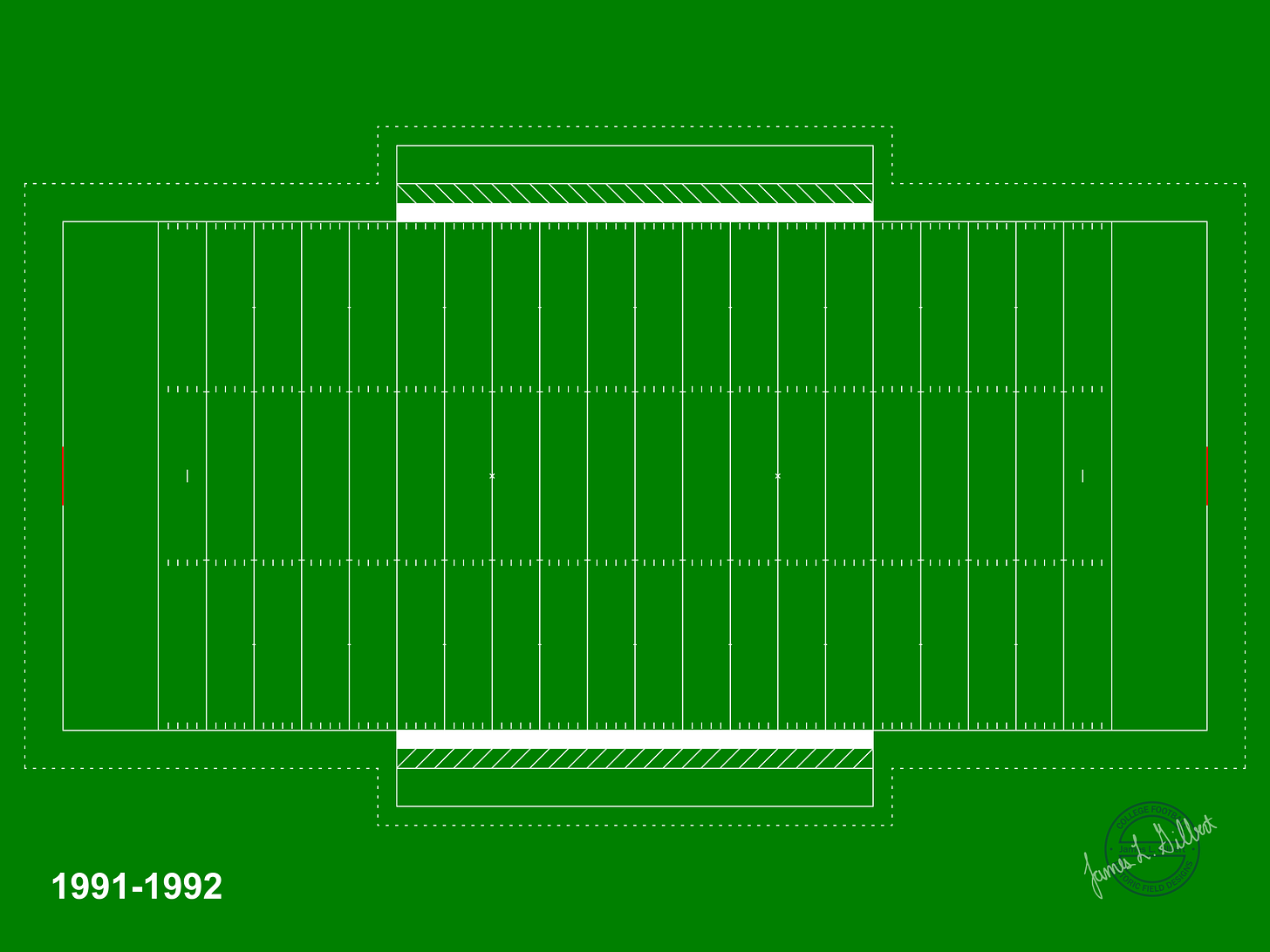

Unable to find complete rule books, I’ve relied on printed rules where I could find them. Sources included newspapers or in the excerpt above a 1982 Eastern Kentucky preseason publication that states that the NCAA Football Rules Committee specified parameters for the 12-foot limit line (Figure 24.)

In 1982 it was recommended that 6-foot by 4-foot yard-line numbers be centered nine yards from the sidelines. This would be approximately half-way between the sidelines and the hash marks.

The team area first appeared in 1957. It expanded once in the 26-seasons before this year (Figure 25). It would not change for the next 38 years.

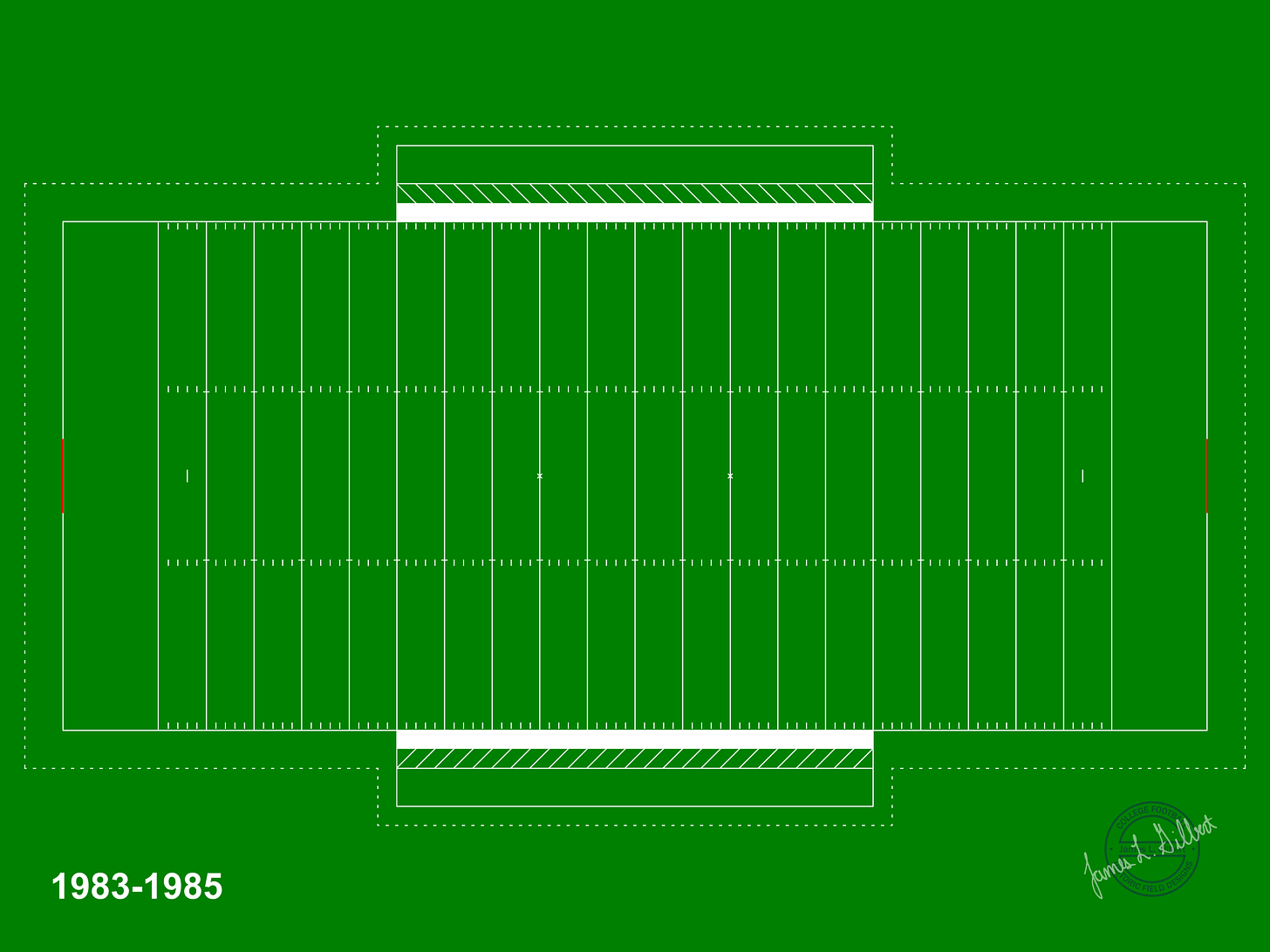

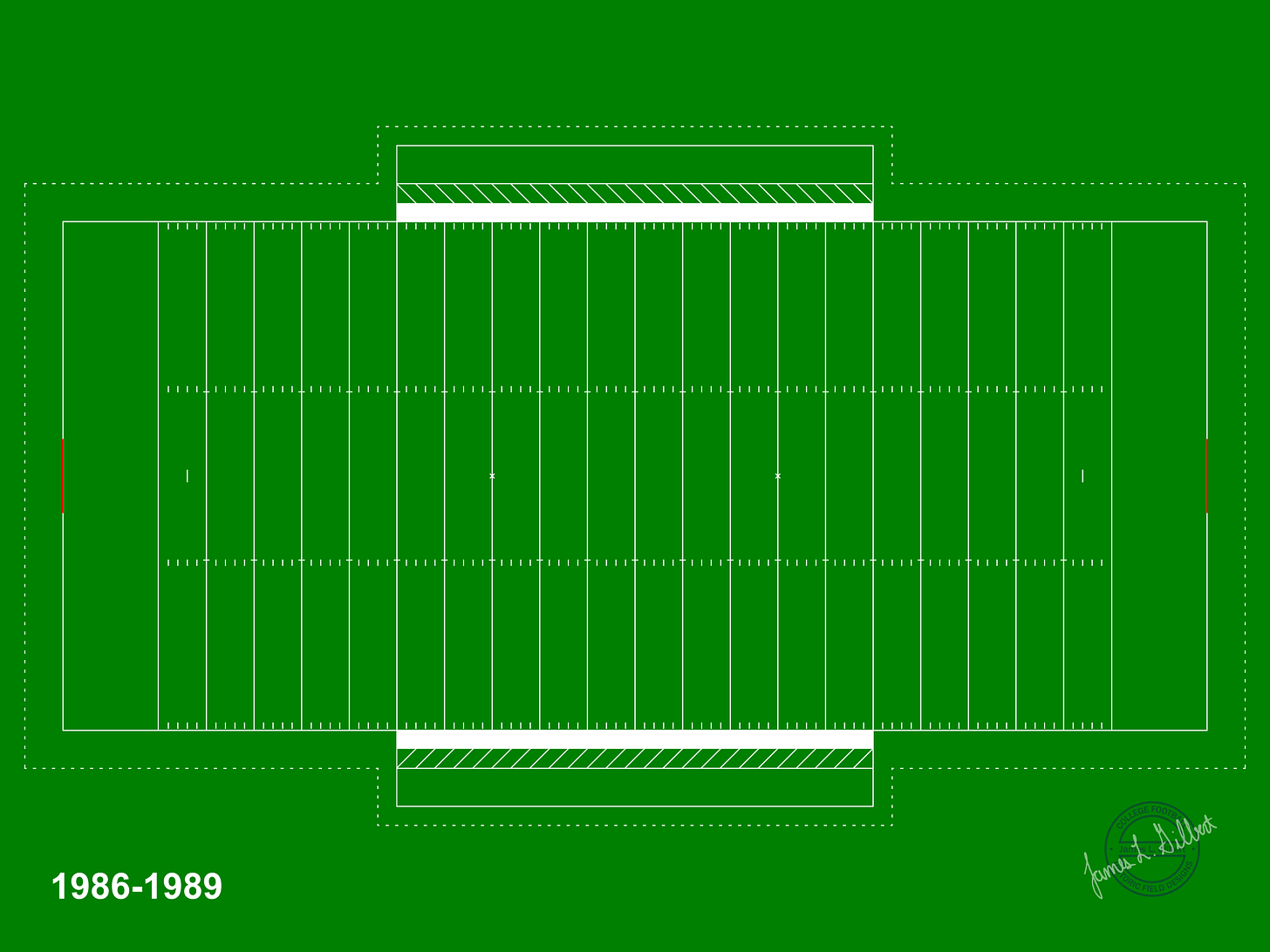

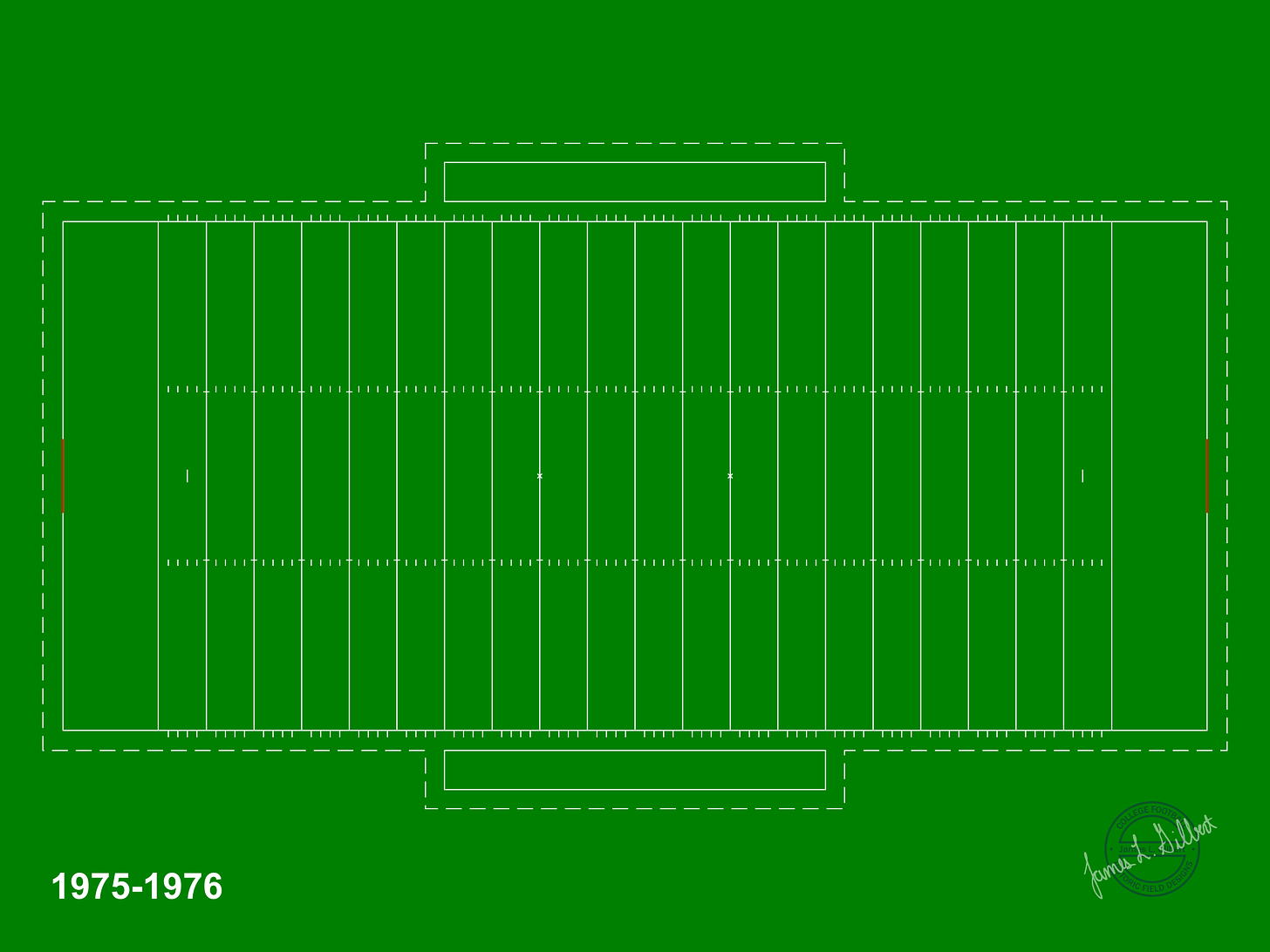

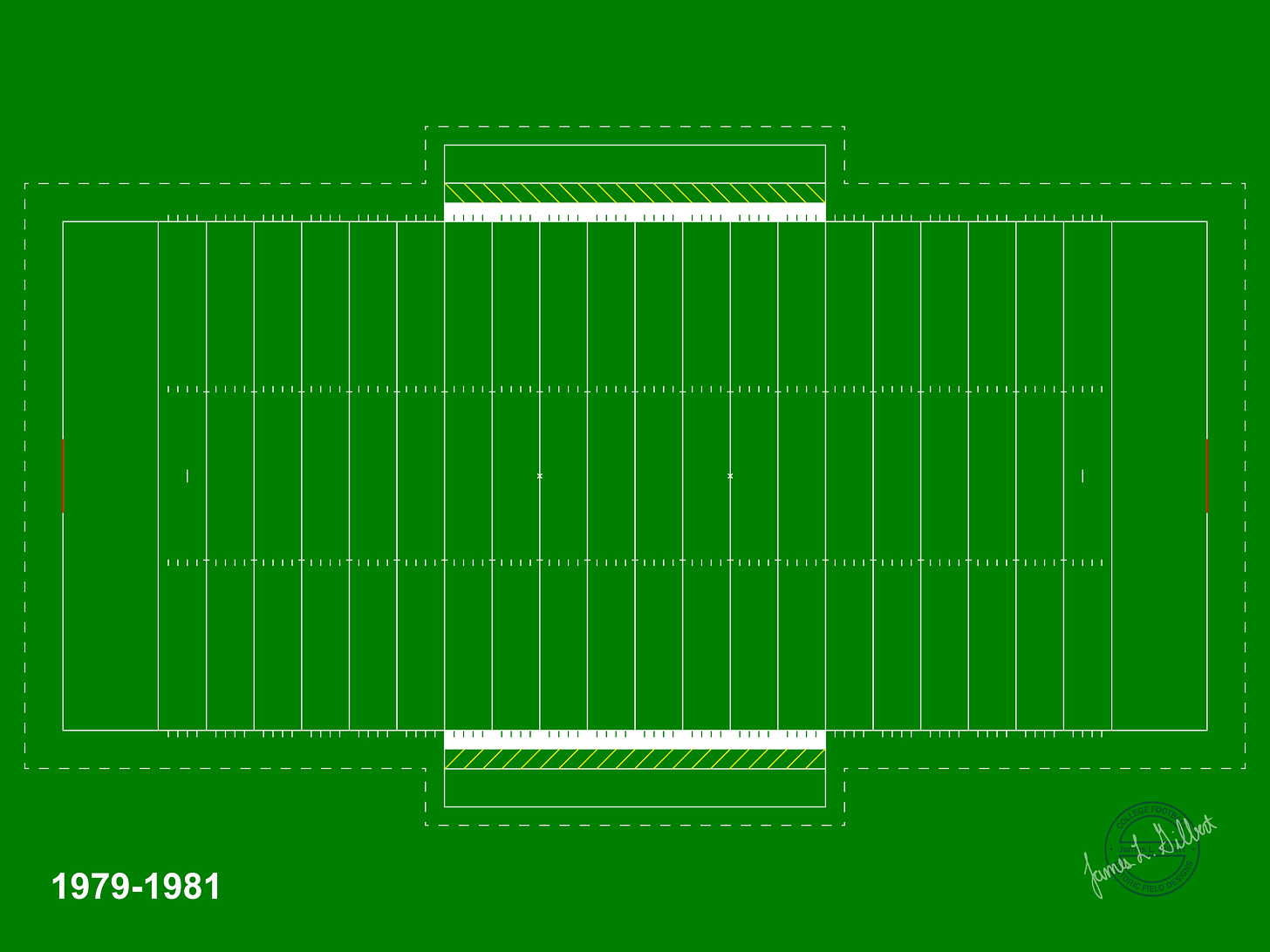

Kickoffs were from the 40-yard line for all but 1 season from 1912-1985. It would remain at the 35-yard line (Figure 26) for all but six seasons since.

The Whole Nine-Yards

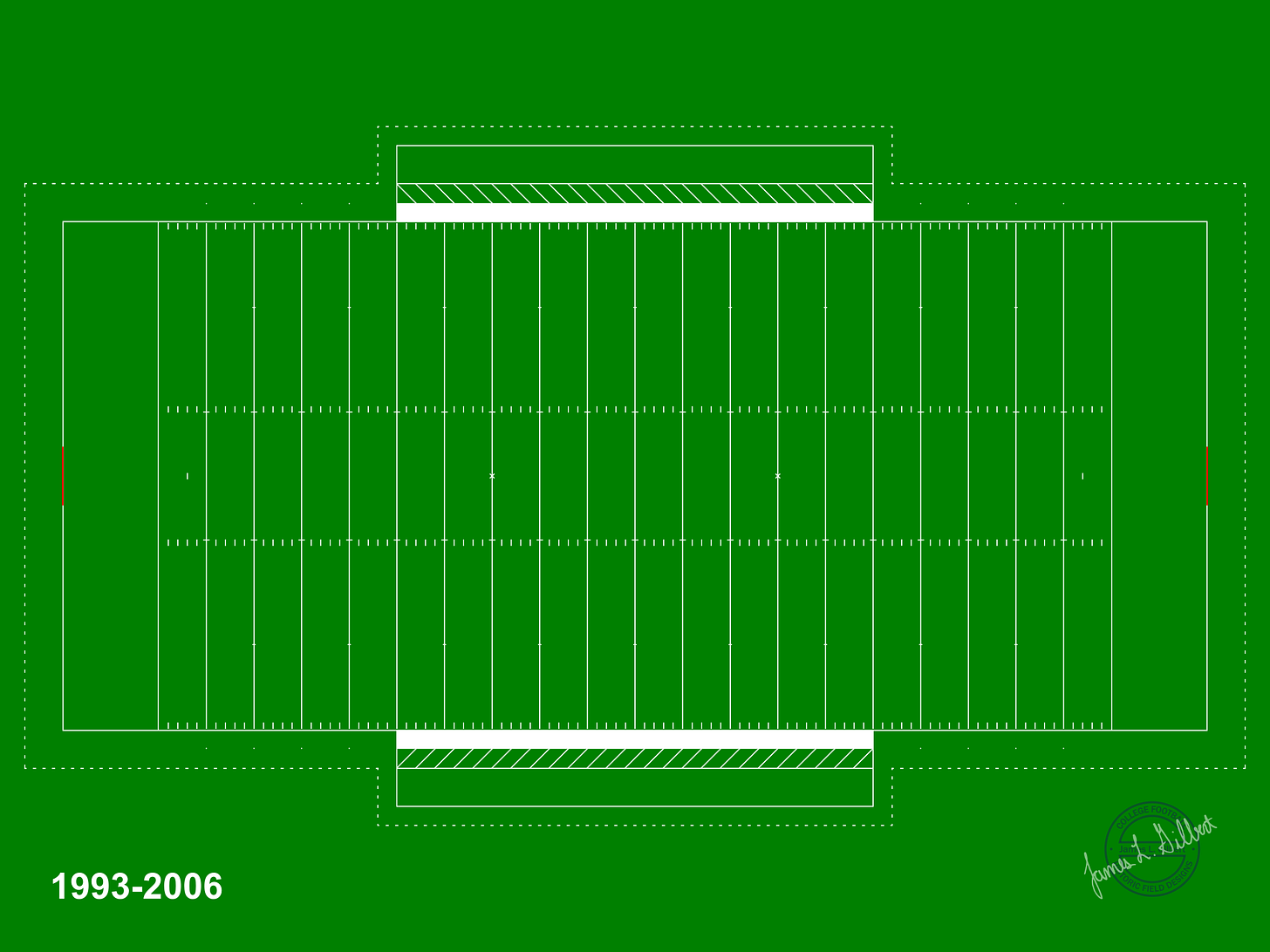

In 1982 the rules committee recommended 6-foot by 4-foot yard-line numbers be centered nine yards from the sideline. In 1990 the recommendation was changed so the tops of the numbers were nine yards from the sideline. This coincided with the adoption of the nine-yard rules. If yard-line numbers are not used (or in the case of NFL fields, in a different location), a 1-foot mark 9-yards from the sideline and every 10-yards is required (Figure 27).

In 1990, this distance was written into the rules as both an inclusion and exclusion zone. Before 1990, in the substitution rules of the day, offensive players had to be within fifteen yards of the ball when it was declared ready for play. If the ball was placed on the far hash a substitute would have to go more than 20-yards onto the field before he could participate. Now the player would only have to go that nine yards. The rules also required that both teams had to be behind the nine-yard marks at the coin toss.

Back to Our Original Goals

With field goals increasing from 120 in 1959 to 2,318 in 1989 and field goal percentage at nearly 70%, the rules committee studied ways to reduce the number of field goals.

After the elimination of kicking tees did not have the desired effect, the committee narrowed the goal posts to the width used for the first 83-years of codified football (Figure 28).

Coaches voted in 1947 to move the hash marks 20-yards inbounds, or 40-feet apart. A continued decrease in scoring and rushing yards per game prompted the rules committee to move the hash marks to diminish any advantage a defense may have in defending a ‘narrow’ side of the field (Figure 29).

Putting the Foot in Football

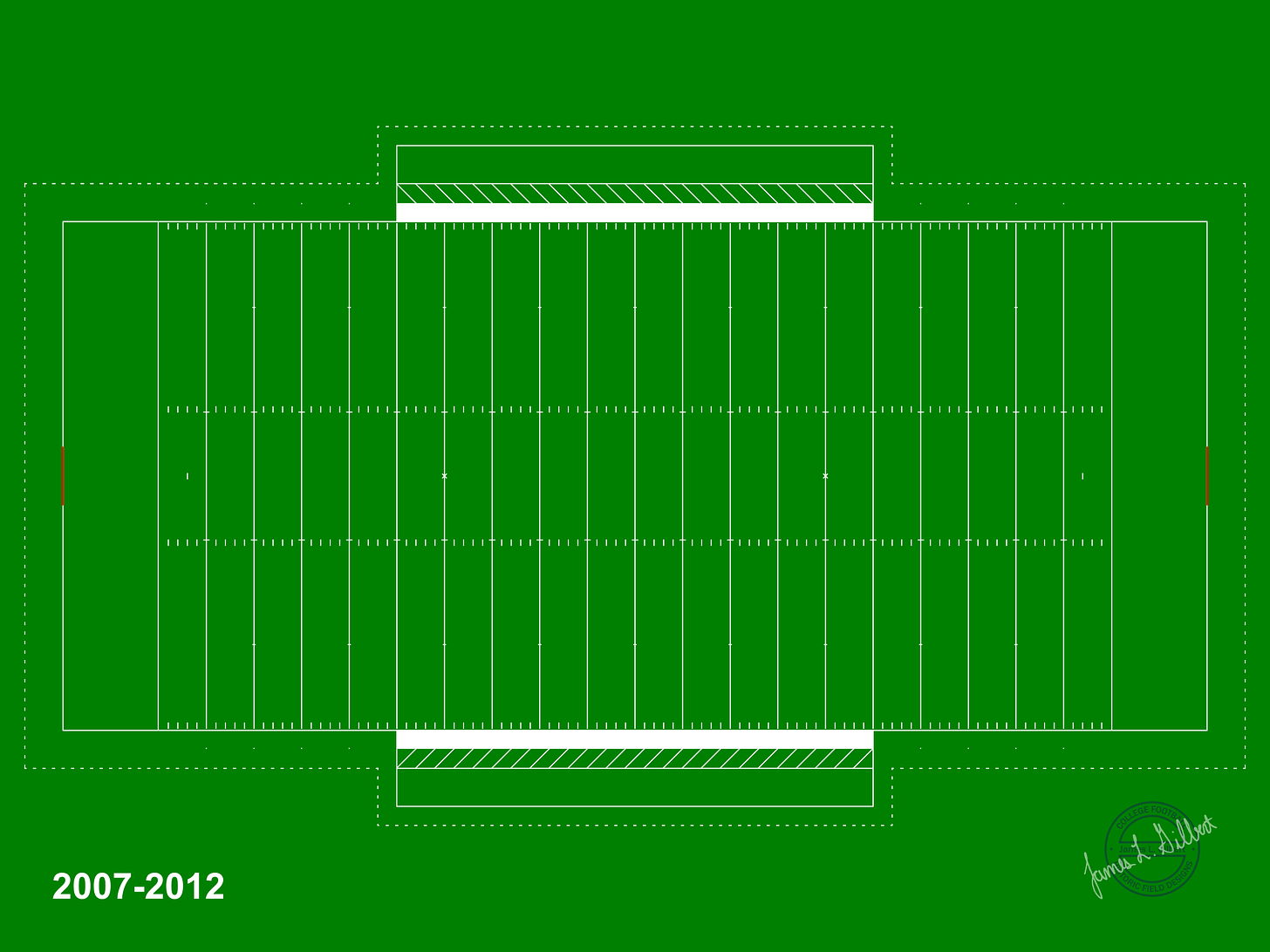

A kickoff return can be a very exciting play. But the ever increasing distance that kickers were able to send the ball on kickoffs meant that touchbacks increased and there were fewer opportunities for these plays. The rules committee did what they always did when they wanted fewer touchbacks on kickoffs, they moved the kickoff yard line (Figure 30).

In addition to being a very exciting play, kickoff returns can also be among the most violent plays on a football field. An emphasis on player safety, which included new rules about fair catches on kickoffs, changed the kickoff location (Figure 31).

Pandemic

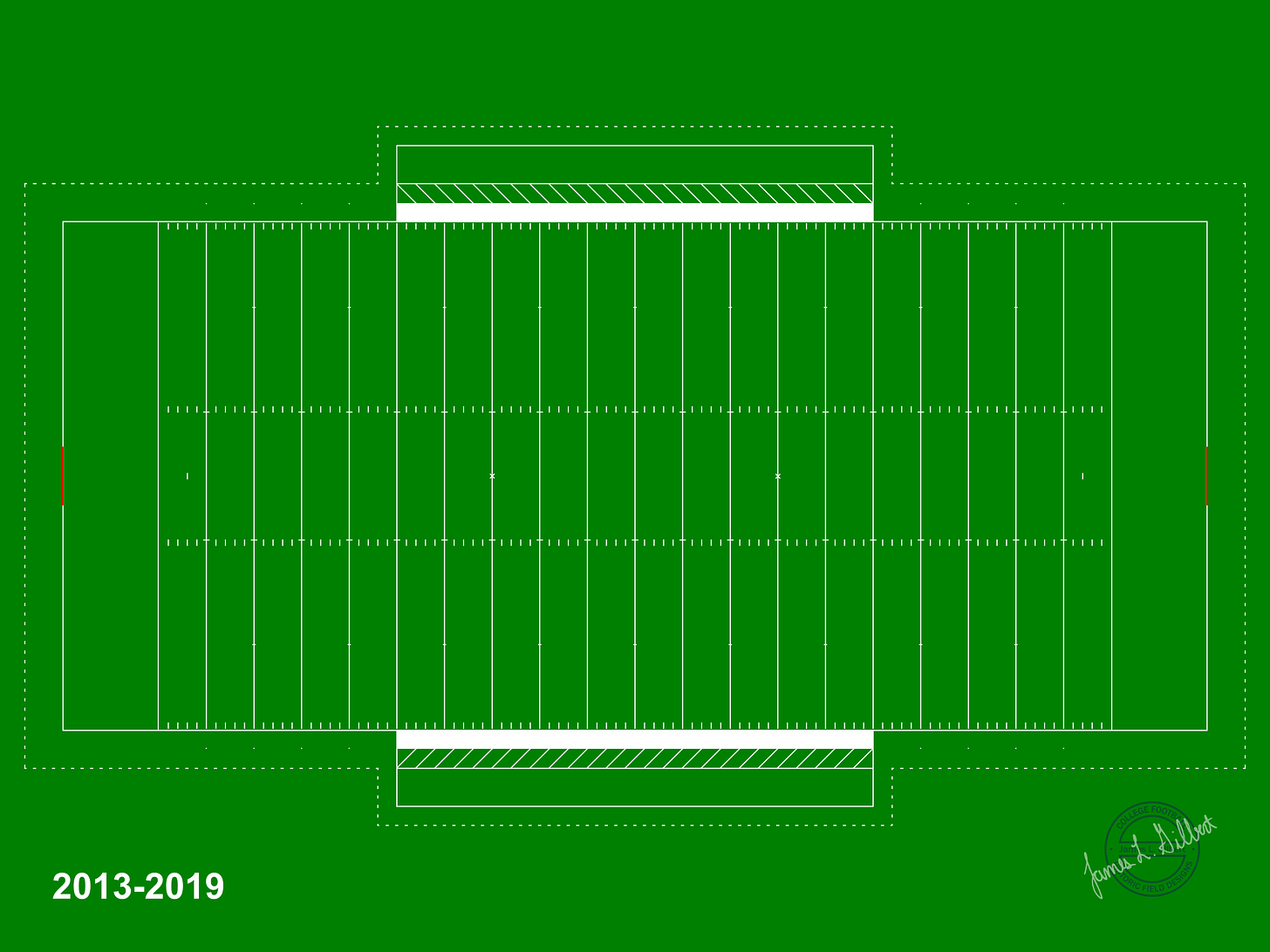

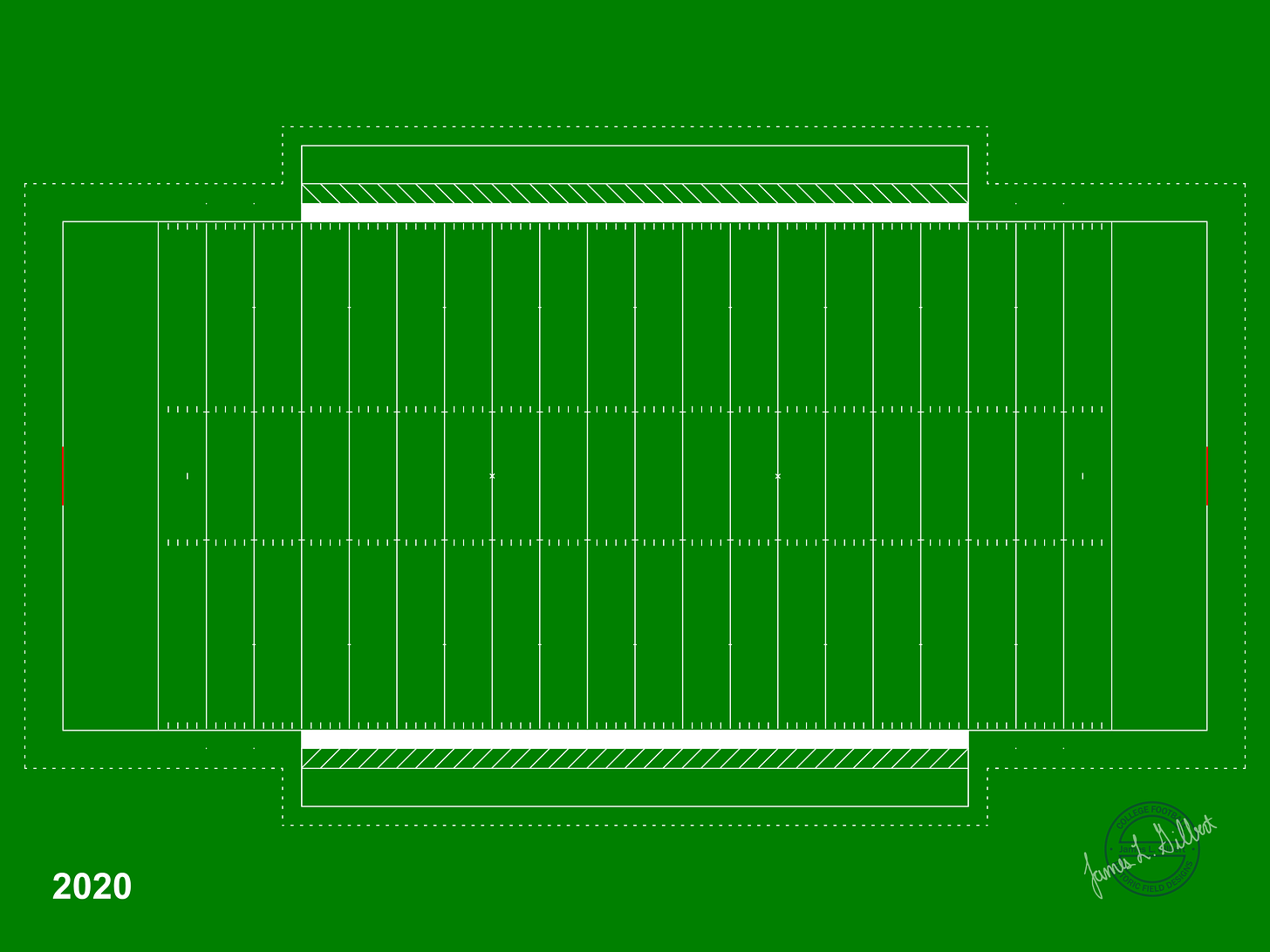

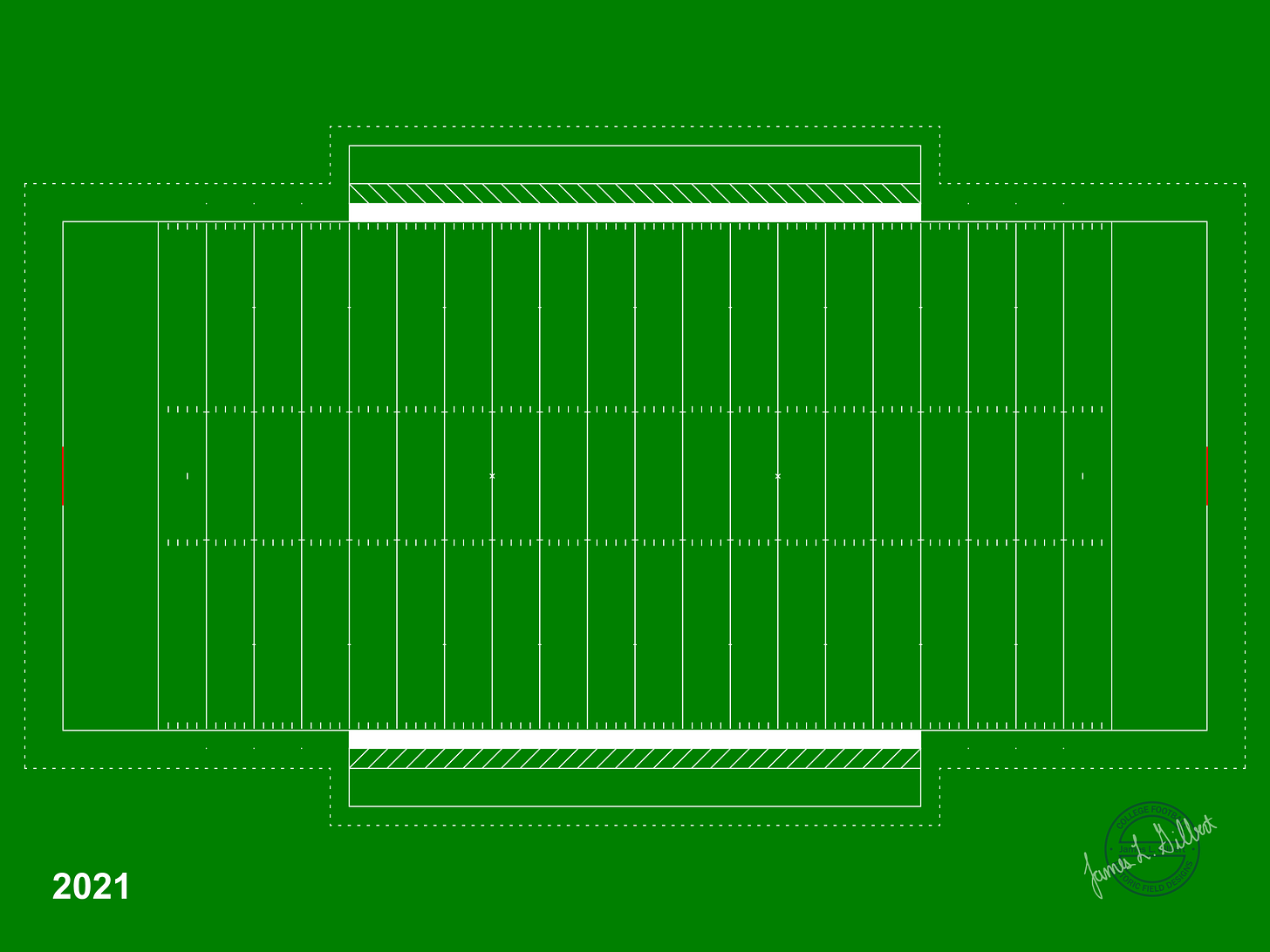

With the proliferation of artificial turf fields since the late 1960s, (fewer than 40 of the 134-bowl subdivision teams in the NCAA play on natural grass) changes to markings are usually planned for future implementation. However, in 2020 it wasn’t apparent that the football season would even occur because of the global pandemic. One response was to expand the team area (Figure 32) which allowed greater distancing on the sidelines. The team area was reduced in 2021 but not back to the pre-pandemic dimensions (Figure 33).

Games and even entire seasons have been cancelled for teams in previous years due to disease outbreaks on campuses and in cities. I’m not aware of any of those issues causing changes in markings on a football field.

NOTE: Several college football fields have a second limit line 3-feet beyond the 12-foot limit line shown in these illustrations. While the NFL requires that line, NCAA rules do not.

It’s possible I’ve missed a required marking or misinterpreted/misidentified a rule. If you’ve got a question or comment I’ll try to respond. Thanks!

That's a great summary. Thanks for posting it.